Monique M. Couture

Partner

Trademark Agent

Article

13

Looking for more insights? This resource is part of a five-installment series. Click here to read our Canadian trademark law year in review for 2021.

Geox S.P.A v. De Luca, 2021 FCA 178

This Federal Court of Appeal decision provides guidance in Section 45 proceedings relating to the importance of vigilance in drafting and updating licensing agreements, and of ensuring that the owner maintains control over the character and quality of the goods or services provided by the licensee.

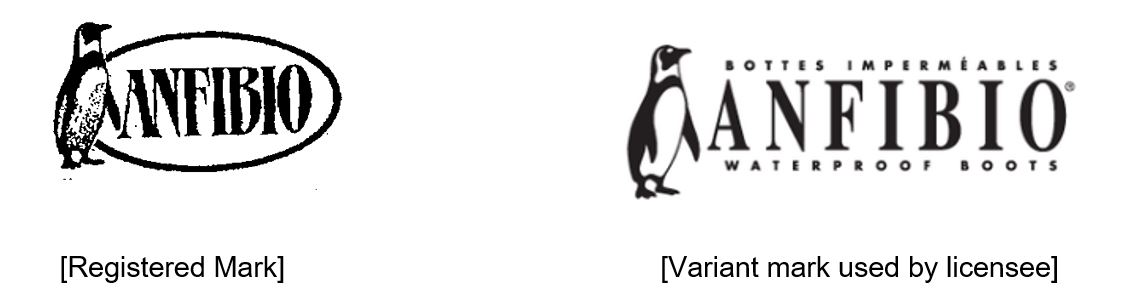

Geox S.p.A. appealed the Federal Court decision dismissing its appeal of a decision by the Registrar upholding the ANFIBIO & Dessin trademark registration. Geox S.p.A. challenged the validity of the registration on the basis that De Luca's licensee used a variant of the trade-mark and not the registered mark, and that it did not use the mark in association with the goods "boots" or "shoes."

In upholding the Registrar's decision, the Federal Court found that use of a variant of a mark may constitute valid use of a registered trademark where the deviation from the registered design does not change the distinctiveness of the registered mark in that the mark retains its dominant features and remains recognizable. The Federal Court was not convinced that the variant mark consisted of anything more than a slight variation and held that the variant mark retained the registered mark's dominant features.

Similarly, the Federal Court was not convinced by Geox S.p.A's argument that because the License Agreement did not specifically allow the Licensee to create and use variants of the Mark, that use of a variant could not constitute use of the licensed mark. Geox S.p.A. also challenged the license's quality control provisions.

However, as the licence agreement did have quality control and related termination provisions, and that royalties had been paid throughout, the Federal Court was satisfied that there was implicit consent to use of the variation of the mark, and that this use enured to the trademark owner in association with boots.

This cases raises the notion of vigilance in licensing marks, both in terms of the licensing agreement itself, and of supervising and approving the ongoing use. Modifications of the mark will always be more risky than using the mark as registered.

The Federal Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal with costs.

Tokai of Canada Ltd. V. Kingsford Products Company, LLC, 2021 FC 782

This decision serves as a reminder about the care that must be taken when designing and carrying out surveys.

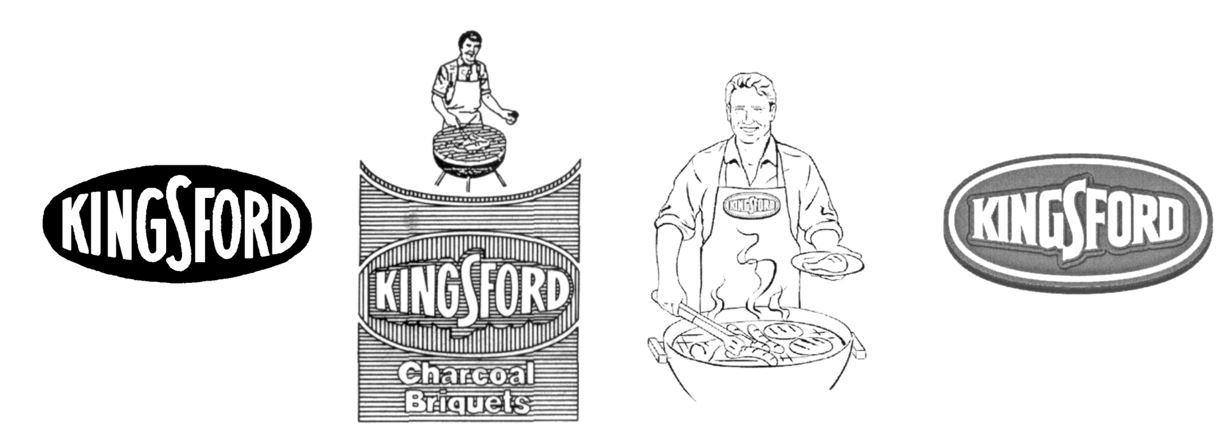

This was an unsuccessful appeal by Tokai to register two marks for KING – one for use with barbecue and fireplace lighters and the other for use with cigarette lighters. The Opposition Board refused the applications on the basis that Tokai's KING marks were confusing with registered marks for KINGFORD for use with charcoal briquettes, and goods relating to barbecuing and/or charcoal, including charcoal lighters. Some of Kingsford's registrations included the following marks:

The Court began by examining the new evidence Tokai sought to file, including the results of a survey. The Court found that there were reliability and validity issues with the survey. In particular, the Court held that: (a) the way in which the term "butane lighters" is used was unclear; (b) the way in which the survey removed answers that were found to be completed too quickly was improper, as these answers could have represented the first impression of a casual consumer somewhat in a hurry; (c) the way in which the survey allowed participants to take hours to complete the survey, as opposed to just 10, 20 or 30 minutes, was problematic, in that it did not guarantee that the survey captured the participants' first impression of the mark; and (d) there were contextual gaps, e.g., when the participants were first shown the mark KING, it was in isolation from anything else, which did not simulate the imperfect recollection of a casual consumer in a hurry at the time when they encounter the relevant trademark in the marketplace. On this basis, the Court held that the survey evidence was inadmissible.

The Court also considered Tokai's additional evidence of eleven third party applications and registrations, which it filed in an attempt to show that KING and KINGSFORD are inherently weak marks. However, the Court held that the eleven third-party trademarks were insufficient to draw any inferences about the state of the marketplace, especially in the absence of any demonstrated marketplace use, and found that this evidence was immaterial.

As the new evidence was either inadmissible or immaterial, the Court reviewed the Opposition Board's decision on the standard of palpable and overriding error and found that there were no palpable and overriding errors. On this basis, the Court dismissed the appeal and awarded costs in the amount of $5,000.

Chartered Professional Accountants of Ontario v. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 2021 FC 35

This decision sheds further light on "Official Marks", a unique creature of statute in Canada which has undergone an erosion of the scope of rights over the last many years. The Federal Court confirms here that an acronym enjoys a limited ambit of protection where no evidence supports the meaning of the acronym at issue.

The Chartered Professional Accountants of Ontario ["CPA Ontario"] appealed a decision from the Registrar of Trademarks rejecting its opposition to the trademark application for "THIS WAY TO CPA" [the "Mark"] filed by the respondent, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants ["AICPA"].

Notably, CPA Ontario became the owner of the official mark CPA only after 2017, while the U.S. accounting designation CPA was used for decades. Qualified Canadian individuals were able to use the U.S. CPA designation for years, well before efforts to transition to a single accounting designation in Ontario began in 2014.

The sole issue on appeal was whether the Registrar made an extricable error of law, or a palpable and overriding error of fact and law, in finding that the Mark does not so nearly resemble CPA Ontario's official mark as to be likely to be mistaken for it under s. 9(1)(n)(iii) of the Trademarks Act. Since the Mark was not identical to CPA, the question was whether the Mark so nearly resembles CPA as to be likely to be mistaken for it. The Federal Court began with a brief overview of the law of resemblance as it pertains to official marks:

Whether a mark is likely to be mistaken for an official mark is not a test of straight comparison, but rather one of resemblance and imperfect recollection: Canadian Olympic Assn. v Olymel, 2000 CanLII 15748 (FC) [Olymel] at paras 26 and 32. Imperfect recollection means the question is approached from the perspective of a notional person who is familiar with the official mark, but who has an imperfect recollection of it: Techniquip Ltd v Canadian Olympic Assn (1998), 1998 CanLII 7573 (FC), 145 FTR 59 at paras 12-16, aff'd (1999), 250 NR 302 (FCA); Canadian Olympic Assn v Health Care Employees Union of Alberta (1992), 46 CPR (3d) 12 at 21-23 (FCTD). The test for likely resemblance to an official mark includes a consideration of the degree of resemblance between the marks in appearance or sound or in the ideas suggested by them: Big Sisters Assn of Ontario v Big Brothers of Canada (1997), 1997 CanLII 16918 (FC), 75 CPR (3d) 177 at 48 (FCTD), aff'd (1999), 1999 CanLII 8094 (FCA), 86 CPR (3d) 504 (FCA)). The degree of resemblance is one of the considerations for assessing the likelihood of confusion between trademarks, under the test set out in section 6(5) of the TMA (specifically, section 6(5)(e)); however, other considerations under the section 6(5) test, including the nature of the goods or services with which the trademarks are used, are not relevant to assessing whether a mark is likely to be mistaken for an official mark.

CPA Ontario argued that the Registrar applied the wrong test of resemblance, looking only at a straight comparison of the Marks' appearance, and failed to consider the same ideas suggested by them. Justice Pallotta was not persuaded:

CPA Ontario submits that the TMOB erred in its application of the test because the TMOB's analysis of the section 12(1)(e) ground of opposition does not address the ideas suggested by the marks. However, the failure to discuss a relevant factor in depth, or even at all, is not itself a sufficient basis for a reviewing court to reconsider the evidence: Housen at para 39. The fact that the TMOB stated the correct test is a strong indication that it applied the correct test, absent some clear sign that the TMOB subsequently varied its approach: Housen at para 40.'

[…]

CPA Ontario also submits the TMOB erred in its application of the resemblance test by failing to consider the dominant or unique aspects of the marks when assessing whether the Mark resembles CPA Ontario's official mark. AICPA notes that CPA Ontario did not make this argument before the TMOB.

As with the ideas suggested, the failure to discuss the dominant or unique aspects of the marks provides an insufficient basis to jettison deference in favour of a correctness review, particularly when the argument was not advanced before the TMOB. More importantly, however, I disagree that the TMOB's approach ignored the dominant or unique aspects of the marks. To the contrary, the CPA element was the focus of the TMOB's section 12(1)(e) analysis.

In summary, I am not persuaded that the TMOB applied a different test for resemblance than the one stated, or that it ignored the dominant aspect of the marks when assessing whether the Mark so nearly resembles as to be likely to be mistaken for CPA Ontario's official mark. CPA Ontario has not established an extricable question of law that warrants review of the TMOB's determination on the correctness standard, and the proper standard of review is palpable and overriding error.

Alternatively, CPA Ontario submitted that the Registrar committed a palpable and overriding error by ignoring the fact that the words THIS WAY TO at the beginning of AICPA's Mark point to or connect to the dominant element, CPA. However, Justice Pallotta noted that the official mark "CPA" consists of letters and does not inherently suggest any specific idea and that CPA Ontario failed to present evidence on its meaning. Moreover, acronyms are only entitled to a narrow ambit of protection:

In its analysis of the section 12(1)(e) ground of opposition, the TMOB noted that the official mark CPA is an acronym consisting of letters of the alphabet. The TMOB referred to case law establishing that acronyms made up of letters of the alphabet are entitled to a narrow ambit of protection: BBM Canada v Research in Motion Limited, 2012 FC 666 at para 40; see also GSW Ltd v Great West Steel Industries Ltd (1975), 22 CPR (2d) 154, [1975] FCJ no 406 at para 32. The TMOB considered and rejected CPA Ontario's argument that CPA should be afforded a wider ambit of protection because it was part of CPA Ontario's family of related official marks, finding that CPA could not benefit from a wider ambit of protection in the absence of any evidence of use of the official marks that made up the family. As a result, the TMOB found that the official mark CPA is entitled to only a narrow ambit of protection, and concluded that the words THIS WAY TO at the beginning of AICPA's Mark rendered it not so nearly resembling CPA as to be likely to be mistaken for it.

The Federal Court of Appeal was not persuaded that the Registrar had committed a palpable and overriding error and therefore dismissed the appeal. Costs were awarded in favor of AICPA in the amount of $7,500.

If you would like to discuss this article further or have any specific questions about it, please contact a member of our Trademarks, Brands & Designs Group.

The authors would like to thank Melissa Cheng, Richard Du, YooJung Jung, Luke Robert and Chloe Ilagan.

NOT LEGAL ADVICE. Information made available on this website in any form is for information purposes only. It is not, and should not be taken as, legal advice. You should not rely on, or take or fail to take any action based upon this information. Never disregard professional legal advice or delay in seeking legal advice because of something you have read on this website. Gowling WLG professionals will be pleased to discuss resolutions to specific legal concerns you may have.