Lidl and Tesco have been at war with one another since Lidl issued proceedings against Tesco, alleging trademark infringement, passing off and copyright infringement. Lidl's focus was on its registered trademark for a yellow circle against a blue rectangular background, which contains the word "Lidl" in the centre (the "Mark with Text"), and Tesco's similar yellow circle and blue rectangular background, but with different text (e.g. price reductions), used in its "Clubcard Prices" promotion launched in September 2020.

In response to Lidl's claims, Tesco filed a counterclaim seeking a declaration of invalidity in relation to Lidl's trademark registrations for its logo, but without the 'LiDL' wording (the "Wordless Marks"). Tesco alleged that the Wordless Marks should be declared invalid on the grounds they had not been put into genuine use and were registered in bad faith.

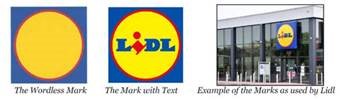

The Marks can be found below:

Lidl Marks

Tesco Marks

These images were taken from the judgement.

In the eagerly anticipated judgment, the High Court ruled predominantly in Lidl's favour. Lidl succeeded on its claim of trademark infringement in respect of the Mark with Text, and in its claims of passing off and copyright infringement. It was held that "Tesco has taken unfair advantage of the distinctive reputation which resides in the Lidl [logo] for low price (discounted) value." Tesco succeeded in invalidating some of Lidl's Wordless Marks for bad faith, but it is clear that Lidl won the day. We look at each claim further below.

Infringement

Lidl alleged trademark infringement by Tesco under section 10(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (the "TMA"), which states:

"a person infringes a registered trademark if he uses in the course of trade, in relation to goods and services, a sign which is identical with or similar to the trademark, where the trademark has a reputation in the United Kingdom and the use of the sign, being without due cause, takes unfair advantage of, or is detrimental to, the distinctive character or the repute of the trademark".

Mrs Justice Joanna Smith focused on the following issues in reaching her decision:

- Addressing the question of whether the marks are "identical or similar": approaching this task by reference to the overall impressions created by the marks and taking into consideration the fact that the 'average consumer' rarely has the opportunity to make a direct comparison between the two marks, the judge was "satisfied that the average consumer perceiving these signs as a whole would regard them as similar". Her analysis in reaching this conclusion focused on the visual and conceptual comparison between the marks, because they would not usually be encountered in a context that involved aural identification. On the visual front, the main difference was the red ring around the yellow circle in the Mark with Text, and the differing words on both marks. Neither party focused their arguments on conceptual similarities and differences, but the differing text obviously created a point of difference. The judge said she was fortified in her view that similarity was established by clear evidence that members of Tesco's internal team (whose job it was to understand and consider the likely perceptions of the average consumer) identified the similarity resulting from the yellow circle on a blue rectangular background.

- Lidl successfully demonstrated the necessary 'link' between Tesco's Clubcard promotion signs and Lidl's trademark in the mind of the average consumer. Mrs Justice Joanna Smith found "clear evidence of both origin and price match confusion/association together with evidence that Tesco appreciated the potential for confusion"; meaning a relevant connection had been established. Individuals at Tesco involved in the development of the Clubcard Prices designs flagged similarity to the Mark with Text, but they were rebuffed on the basis that the desire to use the infringing mark was "non-negotiable" (a position that Tesco failed to address or explain during the trial).

- Mrs Justice Joanna Smith then went on to consider any 'injury' caused to Lidl, and first focused on the 'detriment' alleged by Lidl to have been caused by Tesco to the distinctive character of the Mark with Text. Noting that extra advertising expenditure had been approved by Lidl's board specifically to address the Tesco Clubcard prices campaign, the judge found that Lidl had "established detriment to the distinctive character of its Mark, evidenced by the fact that it has found it necessary to take evasive action in the form of corrective advertising".

- For good measure, Joanna Smith J also considered whether any 'injury' had been caused to Lidl in the form of 'unfair advantage' taken by Tesco of Lidl's reputation in the Mark with Text. She found that "Tesco has taken unfair advantage of the distinctive reputation which resides in the Lidl Marks for low price (discounted) value", with consumers wrongly believing that Tesco were using the infringing mark to show where they had price matched against Lidl products. However, the court also held that there was no subjective intention on behalf of Tesco to achieve this end, rather that Tesco chose the signs with a view to them having "brand significance and influencing their consumers". Further, it found that the use of the infringing mark caused a "subtle but insidious" transfer of image from the Mark with Text to the infringing mark in the minds of some consumers. It may be slightly surprising that no subjective intention had been found given that the evidence clearly showed Tesco were aware of the closeness of the competing marks and chose to use the infringing marks, even though alternatives were considered during the design process.

- Finally, considering whether Tesco nevertheless had 'due cause' for using the Clubcard signs complained of, Joanna Smith J found that Tesco failed to satisfy the burden of establishing this. Tesco argued it had used the colour blue in its branding for some time, and that it was well established that the colour yellow has the best impact for point of sale material. It also highlighted other supermarkets that have used both yellow and yellow circles in their marketing to indicate value propositions. However, none of this evidence satisfied the burden of establishing due cause to extend the use of the yellow value roundel by superimposing it on a blue background.

Mrs Justice Joanna Smith therefore concluded that Lidl's registered Mark with Text had been infringed by Tesco. It is also worth mentioning that Joanna Smith J also found the position on infringement to be the same in relation to the Wordless Mark.

Passing off

Passing off is a common law tort that seeks to protect the "goodwill" of a business, meaning the attractive force that brings in custom. The law of passing off is well settled, with three elements that need to be established: goodwill in the infringed brand; misrepresentation by the infringer as to the origin of their goods and/or services; and resulting damage. Given the success on trademark infringement for Lidl, and the overlap in analysis, the judgment dealt relatively swiftly with the issue of passing off:

- In respect of "goodwill", Lidl claimed (and Tesco did not dispute) that it had acquired valuable and substantial goodwill in the Mark with Text and the Wordless Mark in relation to its business, services and goods. Mrs Justice Joanna Smith agreed, explaining that Lidl has considerable goodwill as a discounter that offers goods at low prices.

- Addressing the misrepresentation element, Lidl argued, and the court agreed, that consumers would have a mistaken belief arising from Tesco's adoption of the infringing mark as to the relationship between Clubcard Prices and Lidl's prices (i.e. that a substantial number of Lidl customers are led to believe that the Clubcard Price is the same or lower than the price offered by Lidl for the equivalent goods). However, again, the court found no intention on Tesco's behalf to misrepresent, despite evidence seeming to suggest the contrary.

- Finally, as a result of finding goodwill and misrepresentation, Mrs Justice Joanna Smith found that Lidl had suffered damage.

Lidl therefore succeeded in its claim against Tesco for passing off.

Copyright infringement

Lidl also claimed that LiDL Stiftung & Co (the second claimant) was the owner of copyright in original artistic works consisting of the Mark with Text. Lidl claimed that the Mark with Text was first published in 1987 and that the copyright expires in 2057.

Tesco rejected the subsistence of copyright in the finished works. It argued that the Mark with Text involved negligible artistic skill and labour and incorporated elements in the form of the blue square and yellow circle created by different authors, such that no principled basis existed to consider the skill and labour involved in the design of those elements per se, together in one copyright work. Mrs Justice Joanna Smith disagreed, saying "it does not follow that, because the fragments taken separately would not be copyright, therefore the whole cannot be". Furthermore, the "simplicity of design and/or a low level of artistic quality does not preclude originality".

The court then addressed the question of whether Tesco copied the Mark with Text. Given the extent of the similarity, the burden fell on Tesco to show that the yellow circle superimposed on the blue background had not been copied. Tesco argued that at no point during the design of the Clubcard promotion sign was there any intention to copy, nor was this suggested to their Design team. Tesco's Brand Design and Format Development Director (Mr Threadkell) provided written evidence in support of Tesco's argument that its Clubcard Prices sign design had been independently created.

However, cross examination exposed that the written evidence provided by Mr Threadkell was incomplete and inaccurate. In particular, Mr Threadkell's written evidence was that all the design work had been undertaken by his in-house Design team, but in cross examination it emerged that a third party design agency (Wolff Olins) had been heavily involved. Tesco had not called the key individual (or anyone) from Wolff Olins to give evidence in the case. Mrs Justice Joanna Smith therefore drew an adverse inference from this, namely that she could "only infer that such evidence would have been adverse to Tesco's case on the development of the design of the Clubcard Promotions sign".

The judge concluded that "Wolff Olins produced a design which Tesco's employees immediately appreciated was likely to cause confusion with Lidl, but Tesco went ahead with the Clubcard Prices promotion in any event". While there may have been no deliberate intention on Tesco's behalf to positively evoke Lidl, this did not mean that the design was not copied; with the focus being adopting the blue and yellow background, which already had a proven association with a strong value proposition.

Tesco's counterclaim – invalidity and revocation

Tesco counterclaimed that Lidl's Wordless Mark should be revoked on the basis of non-use for a period of five years following registration, but was unsuccessful on this point.

Unusually in modern trademark litigation, in this context Lidl relied upon survey evidence, which the judge concluded carried significant weight. In the survey, a nationally representative demographic was asked, in a very open way, what they thought the image presented to them was. The image presented to them was the sign protected by Lidl's Wordless Marks. The results showed 73% of responses mentioned Lidl alone. On this basis, Mrs Justice Joanna Smith found that the Wordless Marks had acquired the ability to demonstrate exclusive origin, and were perceived by a significant proportion of the relevant class of consumers to indicate the goods and services of Lidl. Further, there had been use (in the Mark with Text) in a form that did not alter the distinctive character of the mark in the form in which it was registered.

Bad faith

Despite all of the above being found in Lidl's favour, Tesco did succeed in another counterclaim: that the registrations for the Wordless Mark in 1995, 2002, 2005, and 2007 were liable to be declared invalid, because each had been applied for in bad faith.

Tesco's case was that Lidl's Wordless Mark had never been used in the form in which it appeared on the register, that it had been designed for the purposes of deployment as a weapon in legal proceedings - not in accordance with the function of being used on goods or services to indicate origin - and that the later registrations for the same mark were "evergreening".

Mrs Justice Joanna Smith, being satisfied that Tesco's pleading had raised a rebuttable presumption of lack of good faith, concluded the onus fell on Lidl to "provide a plausible explanation of its objectives and commercial logic". Lidl's corporate memory of the rationale for seeking registration of the Wordless Mark in 1995 did not appear to have lasted. It was unable to displace the prima facie inference raised by Tesco. Therefore, the 1995 Wordless Mark was deemed invalid because it had been applied for in bad faith.

Similarly, Lidl's evidence could not displace the rebuttable presumption of a lack of good faith for the 2002, 2005 and 2007 registrations for the Wordless Mark. That Lidl might conceivably have had a legitimate commercial strategy was not enough. Those marks were therefore invalid too. However, the 2021 mark survived on the basis that it was not "evergreening", because it had been designed to achieve protection for a version of the Wordless Mark that reflected the brand-colour update undertaken at the end of 2020 by Lidl. Added to this, it was in relation to a broader specification of goods and services, including those the Lidl business had begun to sell in the intervening time since 2007.

What does this mean for brand owners?

Although this case is incredibly fact heavy and specific, it clearly illustrates the importance of proper brand protection and enforcement, with many aspects of this judgment likely to delight Lidl's marketing team. It highlights that strategy and record keeping are crucial in the protection of a business's reputation and goodwill.

Lidl has a long established headline brand, which it has protected in the form of trademarks. When its rights appeared to be infringed, Lidl took the decision to take on the biggest supermarket in the UK, and won. Lidl succeeded on all counts in respect of its main logo. In addition, Lidl succeeded in its claim for passing based upon its underlying yellow, red and blue sign – that for which the invalidated Wordless Marks were registered.

Tesco, on the other hand, now faces the difficult task of trying to find a new logo for their Clubcard Prices promotion, and will face a substantial legal bill and, most likely, a claim for monetary relief by Lidl. The creative process employed by Tesco behind the Clubcard Prices promotion, as it emerged in the litigation, also flags the need for all members of a design team to record processes and engage with concerns raised by informed individuals. The lack of evidence in support of Tesco's case of independent design resulted in an adverse inference being drawn by the judge and Lidl's claim for copyright infringement succeeding. Design processes, including who came up with what, and when, should be recorded in detail to avoid a situation where you struggle to explain the design process for copyright purposes.

The case also serves to remind brand owners that the court will give attempts at evergreening short shrift when a mark is clearly not in use, and there is no real intention ever to use it in the form it appears on the register.

To discuss any of the points raised here or any other queries in relation to trademark law, please get in touch with John Coldham, Charlie Bond or Tasha Cranmer-Brown.