Jon Parker

Partner

Article

60

This article explores if the exclusive rights in a trademark can be obtained in the course of trade without registration and what is the scope of such rights across Canada, China, France, Germany, Russia, UAE and the UK. It also examines the benefits of trademark registration in those jurisdictions and describes some practical steps that both a prior user and a subsequent registrant can take to preserve their rights in a trademark.

The topic of our article is prior rights in a trademark and registered trademarks. Trademark rights are obtained either through registration or use. It is crucially important for a brand owner who is either a prior user or a subsequent registrant of a trademark to be aware of the practical steps he can undertake to prevent monopolising of his mark in a particular jurisdiction.

The Canadian Trademarks Act provides that the registration of a trademark in respect of any goods / services gives to the owner the exclusive right to the use of the mark throughout Canada in respect of those goods or services. However, an application for registration can be opposed and a registration invalidated based on prior use or making known of a confusing trademark or the prior use of a confusing trade name. Any attack based on prior rights must take into account section 17 (1) of the Act which provides:

No application for registration of a trademark that has been advertised in accordance with section 37 shall be refused and no registration of a trademark shall be expunged or amended or held invalid on the ground of any previous use or making known of a confusing trademark or trade name by a person other than the applicant for that registration or his predecessor in title, except at the instance of that other person or his successor in title, and the burden lies on that other person or his successor to establish that he had not abandoned the confusing trademark or trade name at the date of advertisement of the applicant's application.

Accordingly, an attack based on prior use must be by the person with the prior use and that person must establish that its prior use was not abandoned as of the date of advertisement of the application.

While prior use is not an issue during examination of an application, it can be raised as a ground of opposition to an application. Section 16 of the Act provides that an Applicant is not the person entitled to registration if at the filing date of the application or the date of first use claimed in the application the mark was confusing with:

The "made known" provision is seldom used because of the very narrow scope of the definition:

A trademark is deemed to be made known in Canada by a person only if it is used by that person in a country of the Union, other than Canada, in association with goods or services, and

and it has become well known in Canada by reason of the distribution or advertising.

Given that the applicant for registration is seeking an exclusive, national right, it does not matter that the prior use might be localised to one city or region of Canada. Prior use anywhere in Canada can be used to oppose an application. Once the prior use is established, the onus falls to the applicant to satisfy the Opposition Board that there is no reasonable likelihood of confusion.

Once a registration issues, it can be challenged on the basis that it is invalid due to prior use or making known of a confusing trademark or prior use of a confusing trade name subject to a key limitation in section 17 (2) of the Act:

In proceedings commenced after the expiration of five years from the date of registration of a trademark... no registration shall be expunged or amended or held invalid on the ground of the previous use or making known referred to in subsection (1), unless it is established that the person who adopted the registered trademark in Canada did so with knowledge of that previous use or making known.

This section sets a critically important deadline - within five years of the registration date, the attacking party need only prove prior use; after the fifth anniversary of the registration, the attacking party must prove prior use and must also prove that the registrant was aware of the prior use when it adopted its own mark - a difficult test to meet.

Where the registration is more than five years old, and subject to the protection of section 17(2), the Court has jurisdiction under section 21(1) of the Act to permit the prior user to continue to use its mark within a defined territorial area:

Where, in any proceedings respecting a registered trademark the registration of which is entitled to the protection of subsection 17(2), it is made to appear to the Federal Court that one of the parties to the proceedings, other than the registered owner of the trade-mark, had in good faith used a confusing trademark or trade name in Canada before the date of filing of the application for that registration, and the Court considers that it is not contrary to the public interest that the continued use of the confusing trademark or trade name should be permitted in a defined territorial area concurrently with the use of the registered trademark, the Court may, subject to such terms as it deems just, order that the other party may continue to use the confusing trademark or trade name within that area with an adequate specified distinction from the registered trademark.

There has been remarkably little use of this section in Canadian jurisprudence.

Prior rights can be enforced in a common law action for passing off and also under section 7 of the Act, essentially a statutory codification of a passing off action. To succeed in a passing off action against a holder of a registered mark, the prior user must commence a proceeding to seek cancellation of the registration in the Federal Court and, at the same time, allege passing off.

Accordingly, common law rights flowing from prior use are an important element of the Canadian system.

The main problem a foreign entity faces in China is that it is a very strict "first to file" country. This means that the first company to apply for a trademark registration, whether that company is Chinese or foreign, will obtain registration and can prevent others from using the trademark. There is no requirement to have any intention to use the trademark. In some instances a foreign company has entered the Chinese market not only to find out that a competitor has registered the trademark it owns elsewhere in the world, but that the competitor is seeking to enforce it against them and demanding payment to transfer the trademark.

Chinese law does provide grounds for opposing a filed application or cancelling a registered trademark. However, procedures can be costly and time consuming, and to succeed it is often necessary to prove that the initial application was made in bad faith. Being the first to file for registration is always the cheapest and most efficient way to secure a trademark and prevent others from encroaching on your patch.

Applications for trademarks should be filed with the China Trademark Office (CTO) through a recognised agent. The cost of filing is low, but the benefits are substantial. Companies should have dedicated personnel or plan in place to ensure that the key trademarks are registered in China as long as the China market becomes relevant to the business. We are all aware of the saying that "Prevention is better than cure", but it is easier said than done. Even multinational companies with sophisticated in-house legal teams can be negligent or make mistakes. There are numerous high profile cases such as the "iPad" and "Tesla" trademark disputes in China, wherein Apple and Tesla were involved heavily with litigations against the third parties which filed the same mark earlier in China, but ultimately have to pay dear amount of money to take assignment of those marks.

Chinese trademark law utilises the "first-to-file" principle, theoretically granting exclusive rights for trademarks to the entity that applies first, which may cause issues where someone else pre-emptively registers a trademark before you would be able to do so. This article explores the protection and enforcement of unregistered rights, including possible avenues for tackling prior registration by another party.

Registration is the quickest and cheapest method of ensuring trademark protection (taking around 9 months at a cost of $100), particularly given that Chinese trademark law is based upon the first-to-file rule. The starting point is that the Trademark Office will approve and publish the trademark registration of the first applicant to file for registration. Therefore, filing for registration as early as possible is the best way to prevent another party from pre-emptively registering your trademark, which could potentially prevent you from using your trademark in China.

Use of an unregistered trademark could also lead to incurring potential liability from another party who does file for registration, which includes payment of damages or fines, seizure of infringing products, injunctions, or even criminal sanctions. Alongside filing for registration of trademark rights as soon as possible, it is therefore also advisable to establish whether there has been a prior registration before using any mark in China.

If more than one applicant applies to register identical or similar marks for the same or homogenous goods on the same day, the Trademark Office will consider the proof of first use in making their decision on registration approval. If neither of the marks have been used, a settlement must be reached between the parties within 30 days for registration to be granted, otherwise where there is no agreement, the outcome will be decided through a lottery.

If another party has pre-emptively filed or even registered your trademark, and you do not have another prior right (such as copyright or design etc.), which could "invalidate" their application or registration, you may raise an opposition/invalidation action under Articles 7, 13, 15 and 32 of the amended Trademark Law, which came into force on May 1, 2014. Article 59 of the amended Trademark Law may also be used as a defence against an infringement action.

The statutes of limitations define a three-month limit for oppositions after a preliminary publication and a five-year limit for invalidations after registration.

Article 7 states that "the principles of honesty and trustworthiness should be followed when a trademark is used and filed for registration." The article may be used to restrain trademark squatting as a means to tackle bad-faith registrations, however this article alone is not sufficient to overturn a registration and should be used in combination with other grounds in order to succeed.

Article 13.2 states "where a trademark in respect of which the application for registration is filed for use for identical or similar goods is a reproduction, imitation or translation of another person's trademark not registered in China and likely to cause confusion, it shall be rejected for registration and prohibited from use". Therefore, if your trademark is well-known in China it is possible to oppose or invalidate the prior trademark and attack the registrant directly for its use, where use of the trademark in relation to similar goods or services would (1) indicate a connection between such goods or services and the owner of the well-known mark, which would likely damage its interests; or (2) diminish the individuality of the trademark or lessen its distinctiveness. The threshold for defining a trademark as being "well known" is extremely high.

Under Article 15.1, if your trademark was not "well-known", however the registrant of the trademark was your representative or agent and applied for such registration in their own name without authorisation, then you can oppose or invalidate the registration and attack the registrant for use of the trademark. Evidence must be provided that you are the original creator and user of the trademark, and that the relationship existed before the filing date.

Article 15.2 applies where you can provide evidence of a contractual or some other form of business relationship and where by reason of such relationship or other related circumstances the registrant knew about the existence of your trademark and registered a similar mark for similar goods or services.

Article 32 does not require the establishment of a relationship with the prior trademark owner. You must demonstrate that the trademark had obtained "a certain influence" through your own use when the prior trademark was filed, and that the applicant pre-emptively registered the mark in an unfair manner. Such prior rights in a trademark or commercial sign include copyright, prior name rights, trade name rights and patent rights, with conflicts between trademarks and prior copyright being common.

The balance between demonstrating reputation and bad faith tilts depending on the evidence of each. With relatively high influence, there is a lower requirement to prove the applicant's bad faith. Conversely, if the bad faith of the registrant is obvious, then the reputational requirement will be relatively lower.

Article 59 also provides a defence against being sued for infringement and allows continued use of an unregistered mark without infringement liability. According to the Article, the unregistered mark must have already acquired a certain level of influence before the filing date of the registrant, the further use of the mark must be restricted to the "original scope of use", where protection against customer confusion is necessary, the registrant has the right to ask for the addition of an appropriate distinguishing mark. Reliance on this article, however, remains risky in part because the "original scope of use" has not been clearly defined.

China's Anti-Unfair Competition Law also provides a form of protection for unregistered trademarks or trade logos, where the name or trade dress is particular to a well-known product. However the scope of this recourse is limited. It is difficult to exploit and most often requires resort to evidence-intensive civil suits.

Businesses intending to utilise trademarks in the Chinese market should conduct searches to find out whether identical or similar trademarks have already been registered in China, before using any mark. The best method of protection of trademarks is to register such marks as soon as possible, and it would be wise to also retain evidence of trademarks being well-known abroad. Whilst punishment of past infringements may be difficult, this will provide an effective basis to take legal measures against future infringements. Where there has been a pre-emptive registration by another party, the Trademark Law provides several avenues of recourse and local legal expertise should be sought in order to bring opposition/invalidation proceedings as well as to assert your own rights.

Under French law, registration grants trademark owners exclusive rights on the registered sign for the goods and services designated in the filing[1].

More precisely, unless authorised by the trademark owner, third parties are prohibited to use:

As a general rule, trademark rights may only be obtained through registration before the relevant office i.e. the French Office (INPI) for French trademarks and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) for European trademarks.

However, protection for trademarks - although they are not registered - is also granted under French law for well-known trademarks, within the meaning of Article 6bis of the Paris Convention.

The protection is granted subject to:

As for registered trademarks, the owners of a well-known trademarks may enforce their rights through invalidity proceedings before the courts[5] or opposition proceedings before the French Office[6].

To that end, the opponent shall demonstrate that its trademark is entitled to the specific protection of well-known trademarks and, in particular, that, on the filing date of the opposition[7], the sign is used as an indication of the product's origin and is known as such by a large segment of the public[8].

However, owners often have difficulties to pass this test and the well-known character of a sign is only recognised in one third of the cases.

For instance, in a recent case regarding the trademark application (see fig. 1), the French Office rejected the opposition filed on the basis of the well-known figurative trademark representing Batman's mask[9]. The French Office held that, although evidence filed by DC comics was likely to establish the ownership of Batman character, as well as its use as a trademark, there was no evidence that the Batman's mask itself was used as a trademark and broadly known by the French consumers within the meaning of Article 6 of the Paris Convention.

Fig.1

If the sign qualifies as a well-known trademark, it is protected in the same manner as a registered trademark. Thus, its owner will also be allowed to initiate trademark infringement proceedings before the trademark court.

However, as for the French Office, French case-law analysis shows that the well-known character of a trademark is hardly established.

For instance, in a case involving a famous Parisian restaurant, the Court:

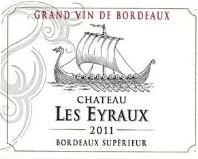

Likewise, in a case involving two wine trademarks the owner of the prior registered trademark (see fig. 2) argued that the use of the sign (see fig. 3) was infringing its trademark.

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

In that order, he claimed that the figurative device representing a boat contained shall be entitled to the protection granted to a well-known trademark. The Court rejected the claim and held that it has not been shown that the figurative device has been independently used as a distinctive sign and acquired as such a well-known character[10].

With an exception to well-known trademarks and registered trademarks, the protection granted to the holders of other distinctive signs, such as company names, trade names or signboards known throughout the national territory and domain names, is ensured through unfair competition and/or parasitism and based on Article 1240 of the Civil Code.

As such, holders must establish:

If the holder succeeds in demonstration of the likelihood of confusion between the prior sign and the later one, French judges can notably cancel the later registered trademark[12], grant injunctions to cease the wrongful acts and monetary damages.

Alternatively or additionally to the initiation of proceedings before courts, the parties may try to amicably settle the dispute and negotiate a co-existence agreement, providing, for instance, for the limitation of the goods and services designated by the later trademark.

In view of the above, both prior users and later registrants should pay close attention to existing signs and regularly monitor third party uses and applications.

In particular:

In Germany, apart from registration of a trademark at the German Patent and Trademark Office (GPTO), trademark protection also arises from

The recognition mentioned in number (1) is acquired on a product-related basis. The required degree of recognition in the specific market can only be determined in relation to the type of mark, taking into account the specific circumstances of the individual case. In the case of a sign with weak distinctiveness, stricter requirements apply for the proof of recognition than in the case of a sign with strong distinctiveness. There are no fixed percentages guaranteeing such recognition.

In the past, in the case of distinctive signs which do not need to be kept freely available, courts have found recognition at around 20-25% to be sufficient (e.g. German Supreme Court, judgement dated 16.10.1959, Case no. I ZR 90/58 "Sunpearl II"; judgement dated 03.05.1963, Case no. Ib ZR 119/61 "Sunkist"), whereas 51.2% of people attributing the sign to the correct manufacturer in a survey were not sufficient for a sign which needed to be kept freely available ("quattro" for a four-wheel drive car; German Supreme Court, judgement dated 21.11.1991, Case no. 1 I ZR 263/89). In its judgement dated 04.09.2003, Case no. I ZR 23/01, the German Supreme Court ruled that recognition by 58% of the total population attributing the unusual colour sign "magenta" to the correct service provider is sufficient to prove recognition for telecommunications services.

Unregistered marks acquired through use differ from registered marks only with regard to their origin and accordingly with regard to the lapse of protection, but not with regard to their scope of protection, in particular with regard to claims against infringers. Trademarks acquired on the basis of market recognition are also part of the assets of a company and can be freely transferred. They are not tied any stronger to a company than the registered trademarks are. It is also generally possible to grant licenses regarding such marks acquired by use. Any resulting change in the view of the relevant market with regard to ownership is legally irrelevant.

Apart from marks that are acquired through use, marks that are not registered with protection in Germany, but that are notoriously well known in the sense of Art. 6bis of the Paris Convention, enjoy protection as a trademark without being registered in Germany due to their high recognition. Well-known marks that are used in Germany will already be protected by means of trademark protection acquired through use, so this additional case only relates to foreign trademarks that are not used in Germany. Notoriously well-known marks enjoy even greater protection than non-well-known marks.

Apart from unregistered marks, company names and work titles enjoy protection under German law which is similar to trademark protection. Company symbols are signs used in the course of trade as a name, company name or special designation of a business operation or an enterprise. Titles of works are the names or special designations of printed publications, cinematic works, music works, stage works or other comparable works. Both company names and work titles come into existence with the use in the course of trade in Germany and subsist as long as they are used in trade.

Prior non-registered rights may form the basis of cancellation actions as well as of opposition proceedings against registered marks. Once a German mark has been registered with the GPTO and the registration has been published, the opposition period of three months starts to run. Within this three-month period, the proprietor of an earlier mark or designation may lodge an opposition against the registration of the trademark.

Apart from registered rights, an opposition can also be based on a non-registered trademark with older seniority as described above or on a commercial designation with older seniority in accordance with Sec. 5 in conjunction with Sec. 12 German Trademark Act. However, it is required that the respective mark or designation entitles their proprietor to prohibit the use of the registered trademark in the entire territory of the Federal Republic of Germany, i.e. such prior rights must not be limited to separate parts of Germany.

A registration may also be cancelled if it is identical with or similar to a trademark with older seniority that is notoriously well known in Germany within the meaning of Article 6bis of the Paris Convention and if the further prerequisites of "identity", "risk of confusion" or "protection of well-known marks" set out in Sec. 9 (1) German Trademark Act are met.

In the course of a cancellation action before the courts, a registered mark can also be cancelled based on other earlier rights, including but not limited to: (1) rights to names, (2) the right of personal portrayal, (3) copyright, (4) names of plant varieties, (5) indications of geographical origin, (6) other industrial property rights.

According to case law, the scope of the trademark protection (to be determined by interpretation) is, in principle, regulated by trademark law. However, in addition to claims under trademark law, claims under fair competition law may exist if they are directed against unfair competitive behaviour that is not the subject of the trademark law regulation as such.

The registration of a trademark is preferable over relying on a mark acquired by use in many different aspects. One main aspect is the burden of proof regarding the existence of the non-registered mark. When asserting rights arising from the mark, the proprietor of a mark acquired through use has to prove its origination through the commencement of use in the market and must also show that the sign has acquired recognition within the relevant public. For this purpose, comprehensive information on type and form, start, duration and scope of use - e.g. by presenting sales documentation, market shares, advertising expenses, price lists, product samples, advertising material and the like may be required. In many cases, a market recognition survey must be carried out and submitted.

Another aspect that needs to be kept in mind is that the five-year grace period during which the use of a registered mark must be commenced does not apply to marks acquired through use, since their protection is acquired on a product-related basis from the outset and their use is a prerequisite for their existence. A mark acquired through use automatically loses its protection as soon as it loses its recognition.

Whenever a sign is of certain importance, we would always recommend applying for trademark registration rather than relying on unregistered rights, but would, nevertheless, want to give some practical advice for proprietors of non-registered marks: It is crucial to collect and store all evidence of use of the mark and include time and place of use and documents that show investment and marketing efforts - not only for the past five years as it is usually recommended for registered marks, but starting from the very beginning of the use. This is essential because the proprietor has to prove commencement and continuation of use and recognition of the mark in all cases he/she would like to rely on the mark. Even if the proprietor later on decides to register the mark, the documentation must still be kept in order to secure the option of asserting rights arising from the prior use with regard to the earlier priority date of the mark acquired by use.

Generally, an exclusive right to a trademark is obtained in Russia through its registration with the Russian Patent Office (ROSPATENT). This is true for regular trademarks and for well-known trademarks.

Even though it is legal to use unregistered marks, companies doing business in Russia prefer to register their core marks as trademarks as early as possible. The benefits that a registered trademark provides to its holder are:

Foreign company names and commercial designations are recognised as a type of IP right without the need for registration. Commercial designations are essentially unregistered business names that may be in actual use.

As a member of the Paris Convention, Russia recognises an exclusive right in a foreign company name without registration. Conversely, companies incorporated in Russia, acquire the right to a company name upon its registration with the Company's Register.

On the other hand, commercial designations provide only very weak rights. As a practical matter, a registered trademark is a much more valuable asset than a commercial designation, because one must collect substantial evidence of longstanding use and notoriety of a commercial designation in order to establish prior rights. A short comparison is as follows:

| Registered Trademark | Commercial designation | |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of protection | Goods/services | Physical location of an enterprise (e.g. a signboard of a coffee-shop) |

| Territory of protection | Territory of Russia | Territory where a commercial designation is renown, e.g. a street or a town |

| Possibility of transfer/licensing | Yes | Can only be transferred/licensed along with the physical location of an enterprise |

| Terms of protection | 10 years with a possibility of extension | Expires if not used during a year |

| Proof of existence | Trademark certificate | Evidence of use |

A prior user who fails to register the mark can lose the right to use it in commerce if the subsequent registrant is granted protection for an identical or confusingly similar mark for the same ICGS classes.

A prior user has limited options to prevent monopolising of his mark by the subsequent registrant. First, a prior user can attempt to block registration of the mark at the ROSPATENT by reason of the misleading character of the mark. Second, a prior user can also challenge the bad faith registration of a mark on the grounds of unfair competition or abuse of right.

According to Art. 1483(3)(1) of the Russian Civil Code, no trademark registration may be granted for a mark that is or comprises elements that are false or mislead consumers as to the manufacturer of a product. In other words, ROSPATENT should refuse registration of a mark, when consumers associate the mark with the prior user and not with its subsequent registrant.

A prior user is entitled, during prosecution of another person's application, to file written observations with ROSPATENT explaining that the prior user's mark has acquired distinctiveness in the minds of Russian consumers before the priority date of the subject application. Should ROSPATENT nonetheless grant the trademark registration, that decision can be appealed first to the Chamber for Patent Disputes and then to the IP Court. A prior user must show evidence of long-standing and substantial prior use of the mark in commerce in Russia. The following evidence can be collected by a prior user retrospectively to show the acquired distinctiveness of the mark:

In Zeldis v. ROSPATENT (2014), the IP Court refused to overturn ROSPATENT's decision to register the BARSUKOR trademark, despite its confusing similarity with BARSUK - the mark previously in use in Russia by another company, because the prior user failed to provide retrospective results of public opinion polls that could prove the mark's acquired distinctiveness.

According to Art. 1512(2)(6) of the Russian Civil Code, a trademark registration can be challenged at any time during the term of its protection, if the trademark registration is declared to be either an unfair competition or an abuse of right. Trademark cancellation proceedings in ROSPATENT can be initiated by the prior user based on the Federal Antimonopoly Service's (FAS) finding or a court's finding that the right conferred under the trademark registration constitutes unfair competition/abuse of right.

The prohibition of unfair competition in the form of acquisition and use of an exclusive right to a trademark is set out in Art. 14.4 of the Federal law № 135-FZ "On the Protection of Competition". A prior user who wants to cancel a trademark registration obtained by a squatter or a bad faith registrant can file a complaint to the FAS, whose decision can then be appealed to the court. Alternatively, a prior user can apply directly to the commercial court to prove that registration of the trademark constitutes unfair competition. The judicial process to establish unfair competition is more costly and time-consuming than is the administrative process at the FAS.

When deciding whether the registration and use of a trademark constitute unfair competition the following facts are usually material:

Unfair competition can only be established if all of the above mentioned circumstances are established. In Metall Profile Company v. V.I.K. Company (2018), the IP Court found that there was unfair competition by the TEXTURVIK trademark holder, reasoning that a confusingly similar designation TEXTURE was in use by a competitor for homogenous goods and the mark acquired notoriety among consumers prior to its registration.

On the other hand, in Décor LLC v. FAS (2016), the IP Court said that the trademark holder's registration of "GAUDI" mark does not constitute unfair competition, as the registrant was not aware of any prior uses of the mark and his intent to register the mark was legal.

Registration of a trademark with the sole purpose of inflicting harm to a third party is considered an abuse of right in accordance with Art. 10 of the Russian Civil Code. An abuse of right assertion can either be a prior user's defence in a trademark infringement action initiated by a bad faith registrant or it may serve as a separate cause of action. Most often, prior users put forward both arguments: an abuse of right and unfair competition.

A trademark holder's behavior before and after registration of the mark is taken into account by courts in order to reveal the registrant's intent. The registration of the mark would be an act contrary to honest practices if the mark in question can be shown to have acquired notoriety in favour of a prior user and was registered with the sole purpose of pushing the prior user's product out of the market.

At the same time, the trademark holder's conduct after the mark was registered can also substantiate a claim of unfair competition or abuse of right. For example, it would be inappropriate if the party obtained the registration in bad faith and then proceeded to send warning letters to competitors requesting monetary relief or initiated multiple trademark infringement actions to exclude competitors from the market.

In general, a prior user bears a relatively high burden to prove unfair competition/abuse of right by a trademark holder. Russian courts are especially reluctant to recognize trademark registration as an abuse of right or unfair competition when the trademark holder was using the mark before registration along with the prior user. In SOZH Synthesis v. KHIM GROUP (2015), the registrant of the ARCTIKLINE trademark filed an infringement suit against its former business partner. The IP Court dismissed the unfair competition/abuse of rights claims reasoning that even though the trademark owner knew about the prior use of the mark by its business partner he did not intend to freeride on its reputation and had a legitimate interest in registration of the mark.

Russian law provides very limited protection for trademarks that are used in the course of trade without registration. Prior users can try to oppose registration of a mark due to its misleading character or to challenge the registration of the mark on the grounds of unfair competition or abuse of right. However, both options require enormous efforts and investments from a brand owner in collecting required evidence retrospectively. Therefore, the best strategy for the companies doing business in Russia would be to file for trademark registration of core marks as soon as Russia becomes a region of interest.

The UAE is a civil law country and as such registered rights are very important when it comes to taking action against third parties. The certificate acts as physical proof of ownership that the enforcement officials expect to see.

That said, the law does provide recognition for the protection of unregistered rights. Also, the provisions of the Paris Convention apply, such as protection of well-known marks, or protection of trade names.

It is often the case that the burden of proof is significantly higher to prove a complainant has protectable unregistered rights than when relying on a registration. There are fewer enforcement options for an unregistered rights holder compared to a registered rights holder, as demonstrated below:

| Action | Registered TM | Unregistered TM |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative action | Yes | No |

| Customs recordal | Yes | No |

| Police criminal action | Yes | No |

| Civil Court action | Yes | Yes |

So what unregistered trademark protection is available in the UAE?

Article 37 of the Trademarks Law provides for protection of trademark rights. Articles 37(1) and 37(2) deal with the protection of "...a trademark registered pursuant to the law..." and "...a registered trademark owned by another..." respectively. These provisions clearly offer protection to registered marks.

However, Article 37(3) is worded[14] as follows:

Anyone who has sold, or offered for sale or circulation, or possessed with the intention of selling, products bearing a counterfeited or imitated trademark, or a mark placed on them without a right to do so and with knowledge of the fact...

There is no reference to the trademark rights being registered in Article 37(3). If an unregistered trademark owner identifies suspected counterfeits in the UAE, it should be able to take action under these provisions.

Additionally, Article 4 of the UAE law provides protection to "...a trademark that has an international reputation that exceeds the borders of the country from which it originates to other countries...".

However, in practice, an unregistered trademark owner would need to bring an action through the UAE Courts. As a litigation matter, this means the only option open is the most expensive and also often the most time-consuming for the rights holder. If the rights holder had registered trademark rights in the UAE, it could look at the more cost effective and often quicker action through the administrative enforcement authorities, or through the police.

There have been court cases in the UAE where unregistered rights have been recognised and enforced. Due to the privacy issues in the UAE and also the fact that cases are largely non-binding, there are relatively few published cases. We have to rely on cases publicised by the parties/their representatives.

One such case from 2008, involved the "Harrods" trademark. Three connected entities had trade names incorporating the word "Harrods" and one of the entities had also registered the "Harrods" trademark in the UAE. The Courts ultimately held that "Harrods" was a trademark with an international reputation which extended to the UAE. The Court ordered the cancellation of the trademark registration, and de-registration of the three "Harrods" trade names by relying on the provisions of the local law, together with the provisions of the Paris Convention regarding the protection of trade names.

In another matter, which also went to the Court of Cassation, the international rights holder, which did not have any actual use in the UAE, managed to show that it was a well-known trademark with a reputation and that its reputation extended to the UAE. This was based on its operations being in countries where a significant proportion of the UAE expat population came from, and so it would have been known to consumers in the UAE. This hard-fought battle over 10 years ultimately led to the registration of the misappropriated trademark being thwarted, and more significantly, also stopped the ongoing use by the defendant in the UAE.

The evidential burden in this case was significant, with the rights holder having to file numerous legalised documents to support its position. The legalisation charges can be as high as USD 1,500 per document. These costs together with court fees and legal fees for a litigation matter over 10 years show that the costs exposure to the unregistered rights holder was significant and could have been lower with registered rights.

It is possible for an opposition and a cancellation action to be filed based on unregistered rights, but as with court actions, the burden is much higher than if it was based on UAE trademark registrations. The unregistered rights holder can rely on the provisions outlined above under Article 4 of the Act, as well as the Paris Convention. In addition, it could also look at the provisions contained elsewhere in the UAE law to try and stop the registration of a misappropriated mark, such as:

It is important to note that the UAE law contains criminal provisions against the use of a mark which offends certain areas of the law (including Article 3 (2), (9) and (11) above). If the unregistered rights holder succeeds on one of the provisions above, it could be argued that any continued use of the brand by the defendant is a criminal offence under Article 38(1).

A decision from the Ministry/Courts which clearly states that the trademark is not capable of being registered under one of these provisions of Article 3 can be a powerful deterrent combined with these criminal provisions.

Often a trademark has been misappropriated by a third party known to the holder, but the rights holder had not registered its trademark in the UAE. This left the way open for the third party to do so. Companies looking to enter the region should take steps to protect their core marks in their core products/services as early as possible so that any potential partners do not have the opportunity to do so.

This advice also extends to local language versions of your branding. Whilst the laws offer a level of protection, often this is to protect "...mere translations of famous marks or previously registered marks...". We have seen that even where the Arabic brand is a mere translation, the officials in some countries in the region have held that the marks are not confusingly similar, simply on the basis that one is an English word, and the other is an Arabic word. It is therefore recommended that where a company is likely to use an Arabic form of its branding, that it also takes steps to protect that form.

Trademark protection in the UAE and some of its surrounding countries is amongst the most expensive in the world. This is also compounded by the fact that the countries are largely single class jurisdictions for national filings.

It is not uncommon for companies to trade and distribute products without registered trademark protection due to the high costs. This can be a false economy if it later transpires that counterfeits are hitting your bottom line or worst case, that your trademark has been misappropriated by a third party, which is now suing you for infringing its rights. This has happened many times. Even though you may ultimately cancel the misappropriated registration, it can take years and significant sums to resolve and in the meantime, could mean that the key members of your local business, or distributor, are left facing criminal charges for trademark infringement.

Our advice to companies is that it is far more cost-effective for your business to register your trademarks as quickly as possible, so as to prevent them being hijacked and to help you in the fight against infringers and counterfeiters.

Under English law, third parties' earlier rights are relevant both when a brandowner is registering and enforcing later marks. An applicant for a trademark may be unsuccessful in his/her application if another person has earlier rights which conflict with the later mark which is applied for. Equally, after registration, a defendant with an earlier right in a particular locality may have a defence to allegations of infringement made by the owner of a later mark.

Section 5 of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (based on Article 5 of what is now Trade Marks Directive 2015/2436) sets out the 'relative' grounds on which a mark shall not be registered, namely where it conflicts with an earlier mark.

A mark cannot be registered that is:

Section 6 of the Trade Marks Act 1994, sets out that an 'earlier mark' for these purposes is:

Other earlier rights

It is not only earlier registered marks which are protected, but also earlier unregistered marks, copyright and design rights. Further, the latest revision to the Trade Marks Directive introduces specific protection for earlier geographical indications.

Unregistered marks, copyright and design rights: Section 5 of the Trade Marks Act provides that a later mark shall not be registered where the use of the later mark is liable to be prevented by virtue of any rule of law protecting unregistered marks or other signs used in trade (in particular, the law of passing off) or by virtue of any other earlier right (in particular, copyright, design right or registered designs).

Designations of origin and geographical indications: Article 5(3) of the recast Trade Marks Directive establishes that a later mark shall not be registered where an application for a designation of origin or a geographical indication has already been submitted prior to the date of application of the mark or the date of the priority claimed, if that designation of origin or geographical indication confers on its owner the right to prohibit the use of a subsequent mark.

Procedure

The relative grounds for refusal can only be invoked in opposition proceedings, or after registration, in invalidation proceedings. When a brandowner applies for a new mark, the UK Intellectual Property Office searches for earlier marks and notifies the owners of earlier marks identified in the search about the new application. The UKIPO will only refuse an application for a trademark on relative grounds if the owner of the earlier mark successfully opposes the mark. It is therefore for the owners of the earlier marks to decide whether they wish to challenge the application through the opposition procedure, or after registration, faced with an enforcement action, via a counterclaim for invalidity.

A specific defence to infringement is available to defendants who have an earlier right which applies in a particular locality.

What is now Article 14(3) of the Trade Marks Directive provides that:

A trade mark shall not entitle the proprietor to prohibit a third party from using, in the course of trade, an earlier right which only applies in a particular locality, if that right is recognised by the law of the Member State in question and the use of that right is within the limits of the territory in which it is recognised.

Section 11(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 is based on the equivalent provision in the Directive but is worded slightly differently. It states:

A registered trade mark is not infringed by the use in the course of trade in a particular locality of an earlier right which applies only in that locality.

For this purpose, an "earlier right" means an unregistered trade mark or other sign continuously used in relation to goods or services by a person or a predecessor in title of his from a date prior to whichever is the earlier of -

and an earlier right shall be regarded as applying in a locality if, or to the extent that, its use in that locality is protected by virtue of any rule of law (in particular, the law of passing off).

In Caspian Pizza Limited v Shah [2015] EWHC 3567 (IPEC), the first instance judge found that the Claimant had goodwill limited to the locality of the city of Birmingham in England (which did not extend to Worcester, a nearby city) going back to 2001 and the Defendant had goodwill local to Worcester going back to 2004. The Claimant's word mark was filed in 2005 and a device mark in 2010. The judge upheld the Defendant's 11(3) defence despite the fact that the Claimant's use of its mark, then unregistered, pre-dated the acquisition by the Defendant of its 'earlier right.' He took the view that the reference in Section 11(3)(a) to earlier use by the proprietor had to be construed in the light of what is now Article 14(3) of the Directive. The claim was appealed to the Court of Appeal, and although this point was not appealed, the Court of Appeal expressly approved the analysis of the first instance judge.

English law, in line with EU law, accords significant protection to the owners of earlier rights, in the face of the attempted registration and enforcement by the proprietors of later marks. The owners of earlier rights must, however, be pro-active in opposing applications for later conflicting marks; the UKIPO does not protect their interests unilaterally.

Footnotes:

[1] Article L.713-1 of the French code of intellectual property (CIP).

[2] Article L.713-2 and L.713-3 of the CIP.

[3] See for instance: Paris Court of First Instance, February 01, 2018 n°16/09836 ; Court of First Instance, December 14, 2017, n°15/14224.

[4] Paris, Court of First Instance, February 01, 2018 n°16/09836 ; French Supreme Court, July 10, 2012, n°08-12.010.

[5] Pursuant to Article L.714-3 of the CIP.

[6] Article L.712-4 of the CIP.

[7] Paris, Court of Appeal, December 1, 2015, n°15/07940.

[8] Paris, First Instance Court, January 26, 2018, n° RG 15/10030. French Office, January 30, 2018, n° OPP 17-4339/MAS.

[9] French Office, January 15, 2018, n° OPP 17-4607/BES.

[10] Paris Court of Appeal, October 24, 2017.

[11] For instance: Paris, Court of First Instance, February 01, 2018, n°16/09836.

[12] It being specified that, except for well-known trademarks, holders of distinctive signs that are not registered cannot file opposition proceedings and can only enforce their rights by initiating invalidity proceedings before the competent jurisdictions.

[13] Pursuant to Articles L.714-3 and L.716-5 of the CIP, infringement or invalidity proceedings shall not be admissible if the use of the later trademark has been tolerated for five years by the owner of the prior trademark.

[14] Please note this is an unofficial translation of the original Arabic language law.

CECI NE CONSTITUE PAS UN AVIS JURIDIQUE. L'information qui est présentée dans le site Web sous quelque forme que ce soit est fournie à titre informatif uniquement. Elle ne constitue pas un avis juridique et ne devrait pas être interprétée comme tel. Aucun utilisateur ne devrait prendre ou négliger de prendre des décisions en se fiant uniquement à ces renseignements, ni ignorer les conseils juridiques d'un professionnel ou tarder à consulter un professionnel sur la base de ce qu'il a lu dans ce site Web. Les professionnels de Gowling WLG seront heureux de discuter avec l'utilisateur des différentes options possibles concernant certaines questions juridiques précises.