John Coldham

Partner

Head of Brands and Designs (UK)

Co-leader of Retail & Leisure Sector (UK)

Article

23

Designs are key assets for many businesses and there are several aspects that are vital to success. In this guide from our Designs for Life series, we take a look at different types of protection.

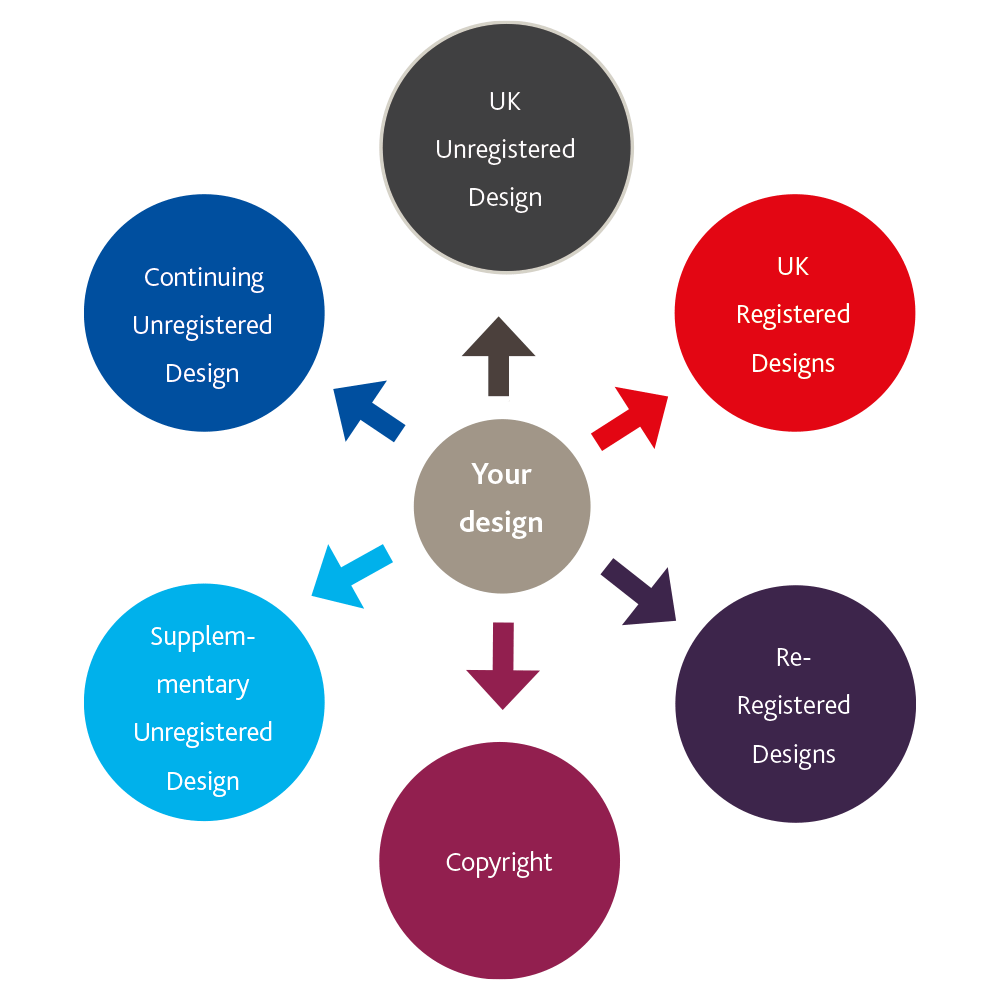

In the United Kingdom, a creator of a design has access to a number of forms of design protection. Protection can include registered and unregistered forms of design right and associated rights such as copyright. The table below sets out the different forms of designs protection available in the UK. However, for more detail, the qualification criteria for the respective rights and a consideration of the overlap between design rights and copyright, please see our Registered Rights table.

There are a number of ways in which your design can be protected currently available in the UK:

The below rights will subsist automatically providing the qualification criteria is met.

| Right | UK Unregistered Design Right (UKUDR) | Supplementary Unregistered Design Right (SUDR) | Continuing Unregistered Community Design | Copyright |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Term | Shorter of 10 years from the first marketing of the product; or 15 years from creation of the design[1]. The final five years of the term are subject to a licence of right | Three years from the date the design is first disclosed in the UK, provided this was on or after 1 January 2021[4] | Three years from the date the design was first disclosed in the UK/EU, provided this was on or prior to 31 December 2020[7] | 79 years from the death of the author/designer[9] |

| Protection covers | The shape or configuration (whether internal or external) of a product[2] | The appearance of a product resulting from (in particular) its lines, contours, colours, shape, texture and/or materials of the product and/or its ornamentation[5] | The appearance of a product resulting from (in particular) its lines, contours, colours, shape, texture and/or materials of the product and/or its ornamentation[8] | Artistic works |

| Arises automatically? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Qualification requirements? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Infringement requires copying? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Infringed by | Infringed by copying the design so as to produce articles exactly or substantially to that design[3] | Infringed by copying the design so as to produce a design which does not produce a different overall impression to the original design[6] | Infringed by copying the design so as to produce a design which does not produce a different overall impression to the original design | Infringed by copying the whole or a substantial part of the copyright work (assessed qualitatively)[10] |

In addition to the above automatic rights, designers may decide to seek enhanced protection by registering the design. This decision will hinge on many variables, some of which are discussed in our "Registration" guide.

| Right | UK Registered Design (UKUD) | Re-registered Design (RRD) |

|---|---|---|

| Term | Up to 25 years (subject to five yearly renewal fees)[7] | Up to 25 years (subject to five yearly renewal fees), provided the parent "Registered Community Design" had been granted by the EUIPO on or prior to 31 December 2020[14] |

| Protection covers | The appearance of a product resulting from (in particular) its lines, contours, colours, shape, texture and/or materials of the product and/or its ornamentation[12] | The appearance of a product resulting from (in particular) its lines, contours, colours, shape, texture and/or materials of the product and/or its ornamentation[15] |

| Arises automatically? | X | X |

| Qualification requirements? | X | X |

| Infringement requires copying? | X | X |

| Infringed by | Infringed by any design which does not produce a different overall impression to the registered design[13] | Infringed by any design which does not a different overall impression to the registered design[16] |

In addition, designers should consider registration in the EU and elsewhere, many of such rights can be sought following filing of the UK registrations.

Looking first at the unregistered designs:

Point to note: It is clear that design rights can be an incredibly valuable asset when they are properly protected, enforced and exploited. However, unlike trademarks, which can be renewed in perpetuity, the protection afforded by design rights has a limited lifespan.

While this does not present a problem for designs which are only ever intended to have a short lifespan, certain designs (such as classic cars) may become more valuable the older they become. Some even become design "icons". Yet no matter how iconic the design, the term of statutory design protection is absolute. So how can the investment which has been made in the design be protected and the next design "icon" stopped from being copied once its design protection expires?

The most common method of seeking to extend design protection is to make minor changes to the design, sufficient to allow new design protection to be sought. This method is most applicable to designs with a design language which is capable of evolving over time. Incorporating new features which are capable of protection into an existing design may provide extended protection against copycats if the new features are sufficient to afford the new design protection. Prior to applying for design protection, it is therefore sensible to understand from the designer how a design may develop over the course of its lifetime.

There is, however, a significant tension between protecting new design features and ensuring that they are not invalid as a result of the earlier designs. For this reason, the approach is of particularly limited use when seeking to protect designs which are not capable of iterative development, but which are fixed (as is the case with most iconic designs). Nevertheless, even where new designs are likely to be invalid as a result of the earlier designs, registered design rights (which are not examined prior to grant) may deter low level infringement and provide a minimal level of protection.

UKUDRs protect the shape or configuration (whether internal or external) of the whole or part of an article - not the colour, material or surface decoration - whereas registered designs, SUDRs and CUCDs protect the appearance of the whole or a part of a product resulting from the features, in particular the lines, contours, colours, shape, texture and/or materials, of the product itself and/or its ornamentation.

Copyright is primarily concerned with protecting creative and artistic expressions of an original idea.

The protection afforded by the registered designs (UKRD and RRD) and by CUCD and SUDRs stems from European law, and, therefore, has similar validity requirements. To be afforded protection under these rights, the design concerned must be "new" and possess "individual character". There is a good deal of law addressing precisely what is meant by "new" and "individual character", but it can be summarised as follows:

Whereas UKUDR is different; for a UKUDR to be valid, is must be "original" or "commonplace", which can be summarised as follows:

For copyright to subsist, it requires the expression to be "original" - this does not mean that the expression must be original/inventive, just not slavishly copied from another work.

For unregistered design rights, the key question is whether your design qualifies for it. The right only exists if the qualification requirements are satisfied. It is important, therefore, that records are kept to demonstrate how the qualification requirements are satisfied, otherwise it can be difficult to prove later. The rules are quite complex, but for designs created since October 2014, the rules are essentially as follows:

Similarly, qualification is important in relation to copyright. The rules are essentially as follows:

Registered rights provide a monopoly protection, meaning that unlike unregistered rights there is no need to prove the infringer copied your design to succeed.

UKUDRs are infringed when the design is copied so as to produce articles exactly or "substantially" similar to that design, which typically requires a product-by-product comparison. The issue of copying is often also determined with account to the similarity between two designs. For sufficiently similar designs, copying may even be inferred without direct evidence of any copying actually having taken place, and it is then for the accused to prove it did not do so.

CUCD and SUDRs are infringed by any design that does not produce a different overall impression provided the accused design results from copying. Registered designs similarly are infringed by any design that does not produce a different overall impression, but there is no requirement to show that the design has been copied. Intentional copying of a registered design, while knowing or having reason to believe the design is a registered design, is now a criminal offence in the UK. The test is, therefore, whether the potentially infringing product creates a different overall impression. As above, overall impression is judged from the perspective of the informed user (i.e. someone familiar with the products in question, typically a consumer and/ or wholesaler/retailer dealing in the relevant products) and is judged by reviewing the whole product.

For copyright there are a number of grounds for primary infringement, all of which require the work to have been copied (e.g. copying, issuing copies to the public, etc.)

Copying should therefore be avoided at all costs. As a result, it is especially important that records are kept to show that no copying took place, and that (a) the business believes the registered design was invalid and/or (b) the business believes that the design it created did not infringe the earlier design. One way to prove this may be to obtain independent legal advice to this effect (although the courts are yet to determine what would be sufficient in this regard to defend against an accusation of criminal liability).

An innovative design can make a significant contribution to a successful product. However, it is not the only factor which is important. Other intellectual property rights such as trademarks, copyright and patents will frequently contribute to the success of a product. It goes without saying that building a successful brand is important in driving sales, and there are numerous facets to establishing an effective brand identity.

Here, we will focus specifically on how trademarks can be used in relation to the design of the product itself, rather than the branding. However, it is important to remember that an effective strategy will often require a holistic view of both the brand and the product.

Gowling WLG's Brands, Advertising and Designs team is a leading designs law team and are actively involved in shaping designs law. We have acted on a number of the significant, reported designs law cases in the UK over recent years, and have been the proud holders of the MIP Designs Firm of the Year Award for four years (2019 - 2022). We act for a number of design-led clients.

Footnotes:

[1] CDPA, s216(1)(a).

[2] CDPA, s213(2).

[3] CDPA, s226(2).

[4] Community Design Regulation, Article 11(1); The Designs and International Trade Marks (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, Schedule 1 part 1, paragraph 10.

[5] Regulation 6/2002/EC on Community Designs ("Community Design Regulation"), Article 3(a); The Designs and International Trade Marks (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, Schedule 1 part 1, paragraph 4.

[6] Community Design Regulation, Article 10(1); The Designs and International Trade Marks (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, Schedule 1 part 1, paragraph 9.

[7] Community Design Regulation, Article 11(1); The Designs and International Trade Marks (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, Schedule 2, part 1, paragraph 11.

[8] Regulation 6/2002/EC on Community Designs ("Community Design Regulation"), Article 3(a); The Designs and International Trade Marks (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, Schedule 2, part 1, paragraph 5.

[9] UK. Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 ("CDPA") s 12(2).

[10] CDPA, s16(3)(a).

[11] Registered Designs Act 1949 ("RDA") RDA, s8(2).

[12] RDA, s 1(2).

[13] RDA, s 7(1).

[14] Community Design Regulation, Article 12; The Designs and International Trade Marks (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, Schedule 3, paragraph 2; RDA, s 8(2).

[15] Community Design Regulation, Article 3(a); The Designs and International Trade Marks (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, Schedule 3, paragraph 2.

[16] The Designs and International Trade Marks (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, Schedule 3, paragraph 2; RDA, s 7(1).

NOT LEGAL ADVICE. Information made available on this website in any form is for information purposes only. It is not, and should not be taken as, legal advice. You should not rely on, or take or fail to take any action based upon this information. Never disregard professional legal advice or delay in seeking legal advice because of something you have read on this website. Gowling WLG professionals will be pleased to discuss resolutions to specific legal concerns you may have.