Bernardine Adkins

Of Counsel

Article

17

Last week, the UK Government published the National Security & Investment ("NS&I") Bill. In a marked contrast to its 'Global Britain'[1] aspirations in a post Brexit world, the Bill will create a mandatory screening regime for investment in certain "core areas" of the UK economy in which national security risks are considered more likely to arise.

The mandatory regime will have a suspensory effect for those transactions that are subject to the mandatory filing requirement. If the Bill is passed in its current form, it will also be a criminal offence to complete a transaction without first obtaining approval from the Secretary of State for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (currently Alok Sharma). Businesses could also be fined up to £10 million or 5% of their worldwide turnover (whichever is higher).

The Bill proposes to grant the Secretary of State with a "call-in" right - whereby the Government will be able to call-in and review transactions it considers may give rise to national security concerns. Notably, this call-in right will apply retrospectively, with effect from 12 November 2020. Subject to passing through the UK Parliament, the Bill is due to come into effect by early next year.

A voluntary regime is proposed in relation to investments in non-core areas, where these investments satisfy pre-defined 'trigger events'. For these transactions, investors will need to self-assess whether the transaction could give rise to national security concerns. If a transaction is not notified under the voluntary regime, the Secretary of State retains a call-in right for up to six months from the date on which they become aware of the transaction (subject to a 'long stop' date of five years of the date of the acquisition).

Crucially, the NS&I Bill applies to specific sectors of the economy and categories of assets. It is not - despite previous billing - a foreign direct investment ("FDI") screening regime as it does not discriminate based on the location or nationality of an investor.

The proposed investment screening regime under the NS&I Bill will exist concurrently with the Government intervention regimes available under the UK merger control regime (save that the possibility of intervention on national security grounds has been removed).

This article considers the key implications of the proposed new regime for investment in the UK.

The NS&I Bill itself was announced the October 2019 Queen's Speech (made on advent of Boris Johnson's premiership after he succeeded Theresa May as leader of the Conservative party).

The Bill's roots, however, go much deeper. As Alok Sharma noted when announcing the NS&I Bill: "The UK is not alone in making such changes to its regime, which means global investors will be familiar with our approach." That said, the UK is alone in that this regime applies both to domestic and inbound investment.

By contrast, from Australia to North America, countries across the globe have in recent years introduced FDI screening regimes in an attempt to protect key industries from perceived threats of 'harmful' foreign investment.

At EU level, a new regulation establishing a framework for FDI screening (the "FDI Regulation") entered into force on 11 October 2020, and the EU was recently consulted on introducing a new regulatory 'module' aimed at countering foreign subsidies that may facilitate the acquisition of EU companies.[2]

The FDI Regulation lays the groundwork for a harmonised EU-wide approach to FDI screening. The regulation introduces a cooperation mechanism for EU Member States and the European Commission in relation to foreign investments, requires that EU Member States notify the EU of any existing FDI screening regimes, and sets minimum requirements for Member State FDI screening regimes.

Concerns around FDI have in recent years related to investment from Chinese based companies, such as Huawei - which a number of countries (including the UK, US, Australia and New Zealand) have recently banned (or limited) from participating in the development in 5G infrastructure.

China itself passed its own FDI screening law last year, which entered into force in January 2020. That regime sits alongside China's so-called 'negative list' which sets out a list of sectors and infrastructure in which foreign investment is forbidden or limited.

Perhaps ironically, fear of foreign investment from countries with historically restrictive FDI regimes (like China) has prompted nations to implement their own FDI screening regimes. Notwithstanding the passage of the FDI screening law, China has been progressively reducing the number of restrictions on its negative list - permitting greater levels of FDI.

As noted above, if the Bill is enacted in its current form, the Secretary of State will have the right to call-in transactions that completed or are in progress as of 12 November 2020.

The call-in right is limited to situations where they reasonably suspect that:

"Qualifying entity" is broadly defined - and includes any entity (whether or not incorporated) except natural persons. If an entity is incorporated outside of the UK, it will fall within the ambit of a qualifying entity only if it "carries on activities" or "supplies goods or services to persons" in the UK.[3]

The meaning of 'qualifying assets' is equally broad, and includes "land, tangible moveable property, and ideas, information or techniques which have industrial, commercial or other economic value".[4]

The meaning of 'trigger event' depends on whether the transaction involves a qualifying asset, or a qualifying entity. The 'trigger events are:

Trigger event - qualifying entity

The acquisition of control or significant influence over an entity such as the acquisition of:

of the votes or shares in a qualifying entity; or the acquisition of:

Trigger event - qualifying asset

The acquisition of a right or interest in, or in relation to, a qualifying asset that provides the ability to:

Under the NS&I Bill the mandatory regime applies to so-called 'notifiable acquisitions', which are defined as occurring where:

The Bill does not define the 'specified description' but the Government's Statement of Policy Intent says that this will defined by reference to the "core areas" and "core activities" which the Government considers are most likely to give rise to national security risks. The core activities and areas are set out in Table 1.

| Chemicals | Civil Nuclear | Communications | Defence |

| Emergency Services | Energy | Finance | Food |

| Government | Health | Space | Transport |

| Water | Advanced technology | Military and dual-use technology | Direct suppliers to Government and emergency services |

These industries are to be confirmed by way of separate regulations passed under the These industries are to be confirmed by way of separate regulations passed under the NS&I Bill after it is enacted.

Trigger events that do not fall within the ambit of the mandatory regime (e.g. because they do not relate to "core areas" or "core activities", or do not involve the acquisition of an entity) are subject to a voluntary notification regime.

The voluntary regime is not suspensory and so it is possible to complete a transaction without obtaining prior approval. However, the Secretary of State retains a call-in right in relation to non-notified transactions that fall within the scope of the voluntary regime for up to six months from the date on which they became aware of the transaction (subject to a long stop date of five years).

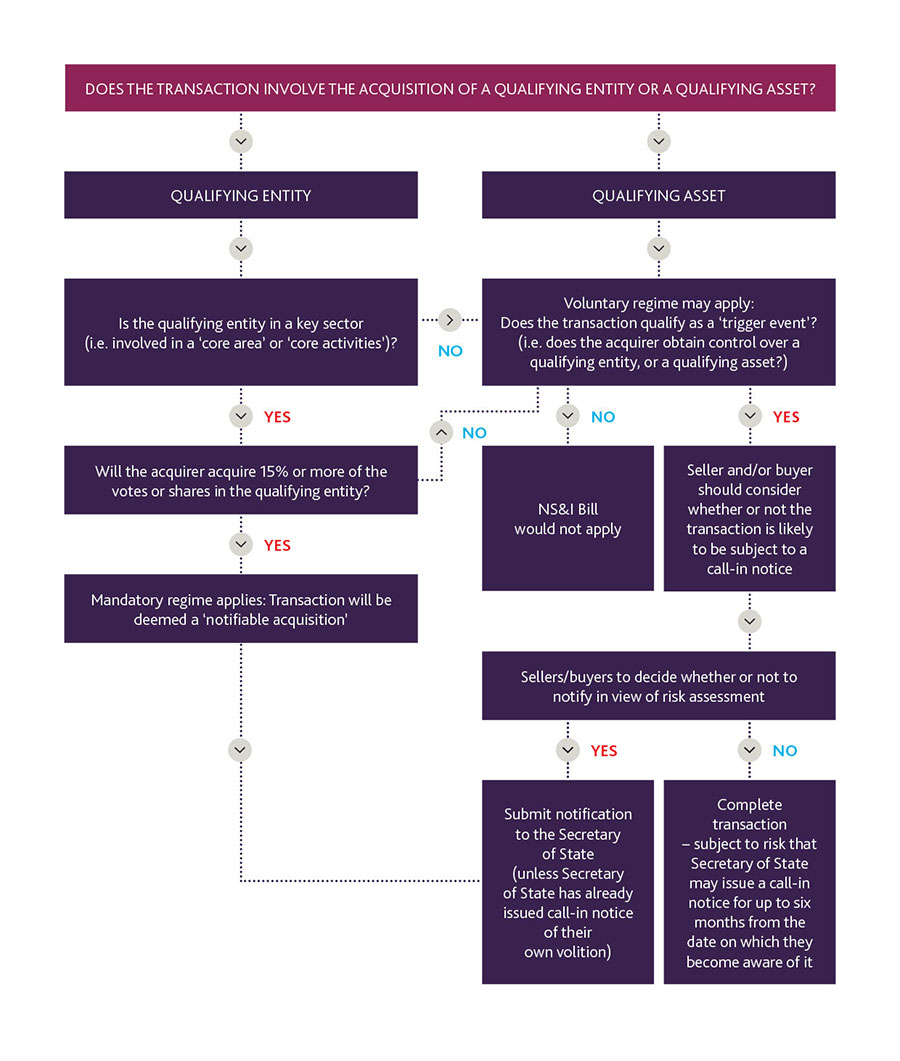

We set out (see Figure 1) the steps that businesses will need to take under the proposed regime in order to assess whether their transactions may be subject to either a mandatory notification requirement or would fall within the voluntary regime.

In view of the retrospective application of the Secretary of State's review right, parties involved in transactions now should already give consideration to whether they may be caught by the new screening regime when the NS&I Bill is enacted.

In either case, the Secretary of State has the power to issue a call-in notice prior to receiving a notification from the parties involved in the transaction. Where the Secretary of State receives a notification under either the mandatory of voluntary regime, they have 30 working days from acceptance of the notification to screen the transaction and decide whether or not to issue a call-in notice. The review process completes if the Secretary of State decides not to issue a call-in notice after the 30 working day screening period, and the transaction will be cleared.

The issuing of a call-in notice triggers a 30 working day 'initial period' in which the Secretary of State will assess whether the transaction could give rise to national security concerns.

This initial period can be unilaterally extended on notice from the Secretary of State by 45 working days, and/or voluntarily extended by agreement with the acquirer. There is no time limit on the length of a voluntary extension of time.

The Secretary of State review process is set out in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Parties assess the transaction (from 12 November 2020)

Figure 2: Secretary of State review process

Footnotes:

[1] Global Britain: delivering on our international ambition

[2] White Paper on Foreign Subsidies

[3] See Clauses 7(2)-7(3) of the NS&I Bill.

[4] See Clause 7(4) of the Bill. This includes trade secrets, databases, source code, algorithms, formulae, designs, plans, drawings and specifications, and software. "Land" and "moveable property" includes property located outside of the UK if it is used in connection with the provisions of goods or services in the UK or in connection with activities carried out in the UK.

NOT LEGAL ADVICE. Information made available on this website in any form is for information purposes only. It is not, and should not be taken as, legal advice. You should not rely on, or take or fail to take any action based upon this information. Never disregard professional legal advice or delay in seeking legal advice because of something you have read on this website. Gowling WLG professionals will be pleased to discuss resolutions to specific legal concerns you may have.