Alexandra Brodie

Partner

IP Litigation

Article

The trademarked three-dimensional shape of the traditional London taxi has been found invalid by the Court of Appeal of England and Wales.

The London Taxi Company (LTC), successor in title to the manufacturer of various London taxi models, sued Ecotive and Frazer Nash Research Limited (FNR) for trademark infringement and passing off based on goodwill in the shapes of the Fairway, TXI, TXII and TX4 London taxi models. Ecotive and FNR are the manufacturers of the "Metrocab", a new hybrid taxi.

Ecotive and FNR denied infringement and challenged the validity of the trademarks, contending that they lack distinctive character and consist exclusively of the shape giving substantial value to the goods.

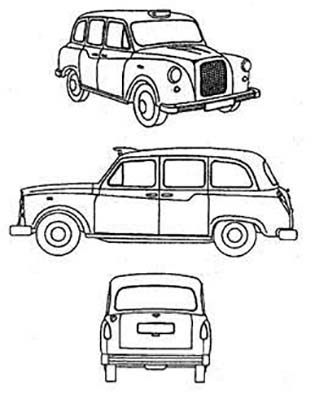

On 5 October 1998, London Taxi Company ("LTC") registered a Community trademark (as shown below on the left) for "motor vehicles" in Class 12, consisting of a three-dimensional mark influenced by the appearance of the Fairways taxi model. LTC also registered a UK trademark based on the TXI and TXII taxi models on 1 December 2006, for taxis in class 12 (as shown below on the right).

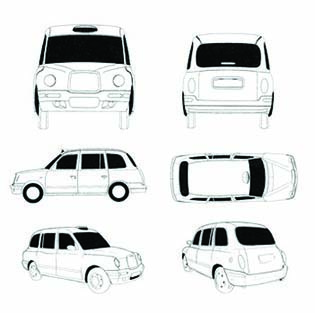

The Defendants' Metrocab at the centre of the dispute is shown below:

LTC sued Ecotive and FNR for infringement of (i) Directive Article 5(1)(b) and Regulation Article 9(1)(b) (infringement where there is a likelihood of confusion); and (ii) Regulation Article 9(1)(c) and Article 5(2) of the Directive (infringement where a mark has goodwill and reputation).

FNR and Ecotive denied infringement, counterclaiming that (a) the marks lacked distinctive character, (b) the marks consisted exclusively of the shape giving substantial value to the goods; and (c) the Community trademark should be revoked for non-use during the five years foregoing the counterclaim.

At first instance, Arnold J concluded that the marks did not have inherent distinctiveness or acquired distinctiveness, and consequently were invalid; the Court of Appeal agreed.

Distinctiveness is assessed from the perspective of the "average consumer". The identity of this notional person gave rise to considerable dispute.

Arnold J concluded that (in accordance with the case put forward by FNR and Ecotive) the average consumer did not include members of the public who hire taxis because they were consumers of taxi services, not taxis.

The Court of Appeal expressed some disagreement. After considering the CJEU's judgments in Case C-371/02 Björnekulla [2004] RPC 45 and Case C-409/12 Backaldrin GmbH [2014] ETMR 30, and the English jurisprudence, particularly Schütz v Delta [2011] EWHC 1712 (Ch), Floyd LJ said that he would be inclined to hold that taxi hirers were not excluded, in principle, from consideration as a relevant class of consumer.

However, this made no difference to the outcome of the assessments of inherent and acquired distinctive character, because the Court of Appeal concluded that:

It followed that LTC's trademarks were invalid. Nevertheless, in case the dispute progressed further, Floyd LJ explained how the Court of Appeal would have addressed the remaining issues.

At first instance, Arnold J found that the marks were invalid in respect of Class 12 goods as their shape added substantial value to the goods.

However, Floyd LJ did not regard as "entirely clear cut" the question of whether, when addressing substantial value, one should take into account or ignore the fact that consumers will recognise the shape as that of a London Taxi, or the existence of design protection in fact. He said that if the Court of Appeal was wrong on lack of distinctive character and these questions were critical to the court's decision, a reference to the CJEU would be necessary.

Article 51 of Directive 2008/95/EC provides that a trademark may be liable for revocation if it has not been put to genuine use within a continuous period of five years. LTC had not produced the Fairway model for up to a decade before the relevant period. The Court of Appeal agreed with the judge that second-hand sales and scrap sales of the old "Fairway" taxi (shown below) did not constitute genuine use.

However, if it were assumed that the trademark had distinctive character, the "small differences" between the mark and LTC's later models of taxi were not, in Floyd LJ's view, such as to alter that character. In other words, if the Court of Appeal's decision on distinctiveness were to be overturned, FNR and Ecotive's application to revoke LTC's trademarks for lack of genuine use would fail.

The issues of infringement were considered on the assumption that the trademarks were valid.

At first instance, Arnold J concluded that no likelihood of confusion existed between LTC's trademark and the new Metrocab. Floyd LJ observed that this was not a surprising conclusion, given that the differences between the trademarks on the one hand and the design of the new Metrocab were quite striking, and "far greater" than the minor evolutionary differences between the models of LTC cab. However, the Court of Appeal refrained from ruling whether, if the registered shape had become highly distinctive as an indication of origin, those differences would have been overcome. Accordingly, if the Court of Appeal's conclusion on distinctive character were overturned, the question of Article 9(1)(b)/Article 5(1)(b) infringement would need revisiting.

On the question of Article 9(1)(c)/Art 5(2) infringement, the first instance judge was overturned. Floyd LJ said that if he had concluded that the LTC marks had an inherent or acquired distinctive character, he would have concluded that the marks had a reputation, and so that the Metrocab infringed for taking unfair advantage of it.

Further, on the assumptions that the mark had distinctive character, a reputation and that there was a likelihood of confusion and/or detriment to the distinctive character of the marks, FNR's Art 12(b)/Art 6(1)(b) defence would fail. Floyd LJ said that he did not see why the rights of the registered proprietor of trademarks which conveyed a clear message about origin should be "trumped" because the marks also conveyed the message that the vehicle was a licensed London taxi. There were other ways of conveying the second message and those ways should then be used to avoid confusion and detriment to the distinctive character of the mark.

The Court of Appeal confirmed the judge's conclusion that there had been no passing off by FNR and Ecvotive.

In the Court of Appeal, the conclusion was reached on the basis that LTC would face the same difficulties in establishing the necessary goodwill for the purposes of its passing off action as it did in relation to showing acquired distinctive character.

LTC's UK and CTM shape marks were found invalid at first and second instance.

However, had they been valid, the Court of Appeal would have concluded that they were infringed. In Floyd LJ's opinion, the outcome of the dispute was rather more finely balanced than suggested by the first instance judge.

On the assumption that the Court of Appeal's judgment is the final word in the dispute, LTC's shape marks represent no barrier to third parties seeking to draw upon aspects of the shape of iconic London taxis when designing a model to compete with LTC's familiar vehicles.

NOT LEGAL ADVICE. Information made available on this website in any form is for information purposes only. It is not, and should not be taken as, legal advice. You should not rely on, or take or fail to take any action based upon this information. Never disregard professional legal advice or delay in seeking legal advice because of something you have read on this website. Gowling WLG professionals will be pleased to discuss resolutions to specific legal concerns you may have.