Adam Chamberlain

Partner

Certified Specialist - Environmental Law; Certified Specialist - Indigenous Legal Issues (Corporate and Commercial)

Article

11

This article was co-authored by Chris Hummel, an articling student at Gowling WLG.

The Arctic has a very long history of avoiding the limelight. But, with the relentless developments related to climate change and escalating rhetoric over territorial sovereignty, the Far North increasingly finds itself at center stage.

As both a bastion of ecology and culture, the Arctic is no stranger to the tension between environmental protection and economic progress. Recent milestones in both Indigenous territorial conservation and international geo-politics highlight the recurring themes that shape Arctic governance, and set the stage for the significant changes that lie ahead.

This is a brief update on three issues of interest in the context of the evolving Arctic.

U.S. politics appear to have made a polar expedition. Earlier in May, the eight countries of the Arctic Council held their 11th Ministerial meeting in Finland to discuss the future of the circumpolar world. The meeting was, in many ways, a changing-of-the-guard. It was the final meeting of the 2017-2019 Chairmanship led by Finland, which ushered in their successor for the 2019-2021 Council Chairmanship: Iceland.[1] However, this news was overshadowed by a different shift in leadership.

For the first time in the Council's 23-year history, the member countries could not agree on a joint declaration. The main reason for this was the United States' refusal to acknowledge climate change and its threats to the Arctic.

For the first time in the Council's 23-year history, the member countries could not agree on a joint declaration. The main reason for this was the United States' refusal to acknowledge climate change and its threats to the Arctic.

The Unites States was represented at the Council by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. If Pompeo's opinion is any indication, the Arctic's future may be defined more by conquest than co-operation:

"In its first two decades, the Arctic Council has had the luxury of focusing almost exclusively on scientific collaboration, on cultural matters, on environmental research-all important themes, very important, and we should continue to do those,

But no longer do we have that luxury of the next hundred years. We're entering a new age of strategic engagement in the Arctic, complete with new threats to the Arctic and its real estate, and to all of our interests in that region."[2]

Pompeo also publicly rejected Canada's assertion of sovereignty over the Northwest Passage, citing the long history of disagreement between the US and Canada over Arctic waters. Pompeo's rebuke provoked a response from the Inuit Circumpolar Council's President Monica Ell-Kanayuk: "the Northwest Passage is part of Inuit Nunangat, our Arctic homeland." Ell-Kanayuk credited Canada's sovereignty in the north to land claims agreements with the Inuit and the 4000-year history of the Inuit in the region.[3]

Finland's term as Council Chair was characterized by commitments to environmental protection, northern connectivity, climate change co-operation and education. Iceland's has expressed an intention to continue those priorities, with an emphasis on sustainable development. The Arctic Council has always advocated for an approach that balances or reconciles these seemingly opposite interests. It remains to be seen whether this approach can prevail in the increasingly acrimonious geo-political climate.

While international geo-politics swirl, Canadian Indigenous groups in the north have embarked on land protection initiatives of a significant scale. In the Northwest Territories, Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve has entered Preliminary Screening following a proposal from Dene and Métis governments. Meanwhile, in Nunavut, Inuit organizations continue negotiations for some of the world's largest marine protected areas.

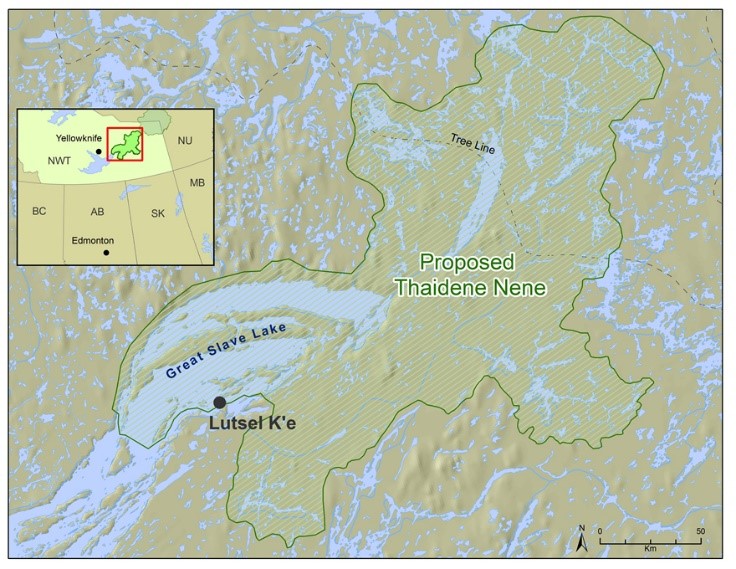

Thaidene Nëné means 'Land of the Ancestors' in the Dënesųłın̨é language. The proposed Thaidene Nëné protected area would span over 26 000 km.2 Of that, 14 000 km2 would form the National Park Reserve land.[4] The proposed area, found northeast of Lutsel K'e First Nation, was proposed by Akaitcho First Nations, Northwest Territory Métis in consultation with Tlicho Government and North Slave Métis Alliance. These Governments are in the middle of negotiating with the Government of Northwest Territories, Parks Canada and various Indigenous Governments.[5]

The park would protect Crown Lands surface and subsurface rights from disposition, but protect existing third party leases.[6] The scale of this park is significant and there are many in the resource extraction sector who are concerned that it will have significant negative implications for the mining sector in the Northwest Territories and the potential growth of high value jobs in the coming decades. This concern is highlighted by the fact that currently operating diamond mines will reach the end of their operating lives in the not too distant future.

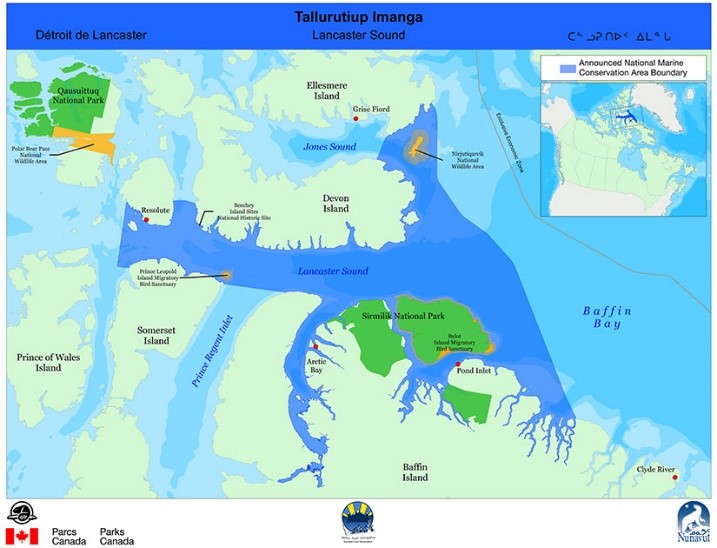

In Nunavut, negotiations continue for Tallurutiup Imanga - one of the world's largest marine protected areas, proposed at 109 000 km2. Tallurutiup Imanga - a joint effort between the Qikiqtani Inuit Association and Parks Canada - would limit submarine oil exploration and establish a Guardian program to integrate traditional knowledge with ecological monitoring and park management.[7] Negotiations have proceeded rapidly and may reach an agreement prior to the upcoming federal election.

For the first time in the Council's 23-year history, the member countries could not agree on a joint declaration. The main reason for this was the United States' refusal to acknowledge climate change and its threats to the Arctic.

Additionally, in April 2019, QIA and Parks Canada announced an intention to negotiate the creation of yet another large marine protected area, known as Tuvaijuittuq, in the High Arctic surrounding Ellesmere Island.[8]

The trend towards northern territorial protection demonstrates a desire to balance development and conservation, and signals the concurrent interests of Indigenous and federal governments in asserting international sovereignty over Arctic lands and waters.

One additional and less discussed issue in the examples described above is the involvement of other stakeholders in these processes. To varying degrees, industry, affected communities and governments have (from time to time) expressed concerns that their input may not have been considered by the principal players in these initiatives. Bringing everyone to the table is not always as easy as it might sound, especially in the massive geography of the Canadian north.

While Canadian federal and Indigenous groups work towards finding common ground on the balance between resource exploitation and territorial protection, American legislatures are starkly divided on protections of the Alaskan coast.

The significant Republican-led tax cuts of 2017 included a provision approving oil and gas development in the Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), which was normally shielded from such activity. The Democratic Congress elected in 2018 has recently advanced a Bill to reinstate the ANWR protections through the Arctic Cultural and Coastal Plain Protection Act.

In the words of US Representative Jared Huffman during the House Committee on Natural Resources:

"This bill reflects a simple proposition, and that is there are some places too wild, too important, too special to be spoiled by oil and gas development…The Arctic refuge coastal plain is one of those special places."

With adjacent lands and waters, and Indigenous cultural overlap between Alaska and Canada, the ANWR is of significance to communities in Northwest Canada. Accordingly, Gwich'in leaders have spoken out in favour of the Democratic bill and attended committee hearings in Washington DC.[9]

However, even if the Bill passes in Congress, it is thought by many to be unlikely to survive a subsequent vote from the Republican-led Senate.

[1] Arctic Council Arctic Council Ministers meet, pass Chairmanship from Finland to Iceland, Arctic States conclude Arctic Council Ministerial meeting by signing a joint statement, (2019 May 31).

[2] Nunatsiaq News, Canadian Inuit challenge US Stance on Northwest Passage, (2019 May 9).

[3] Ibid

[4] Government of the Northwest Territories, Establishment of the Territorial Protected Area of Thaidene Nene under the proposed Protected Areas Act (2019 May)

[5] Mackenzie Valley Review Board, Preliminary Screening of a Proposal to Establish Thaidene Nene National Park, (2019 May 8).

[6] Preliminary Screening of a Proposal to Establish Thaidene Nene National Park

[7] Parks Canada, Parks Canada announces funding to Qikiqtani Inuit Association for pilot Guardian program in Arctic Bay, (2018 July 18).

[8] Nunavut News, More marine protected areas may be on the way near Nunavut northernmost hamlets, (2019 April 19).

[9] Yukon News, US Bill seeking ot shield ANWR from development approved by committee, (2019 May 3).

NOT LEGAL ADVICE. Information made available on this website in any form is for information purposes only. It is not, and should not be taken as, legal advice. You should not rely on, or take or fail to take any action based upon this information. Never disregard professional legal advice or delay in seeking legal advice because of something you have read on this website. Gowling WLG professionals will be pleased to discuss resolutions to specific legal concerns you may have.