Susan H. Abramovitch

Partner

Head - Entertainment & Sports Law Group

Article

8

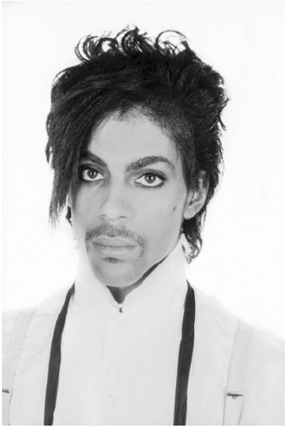

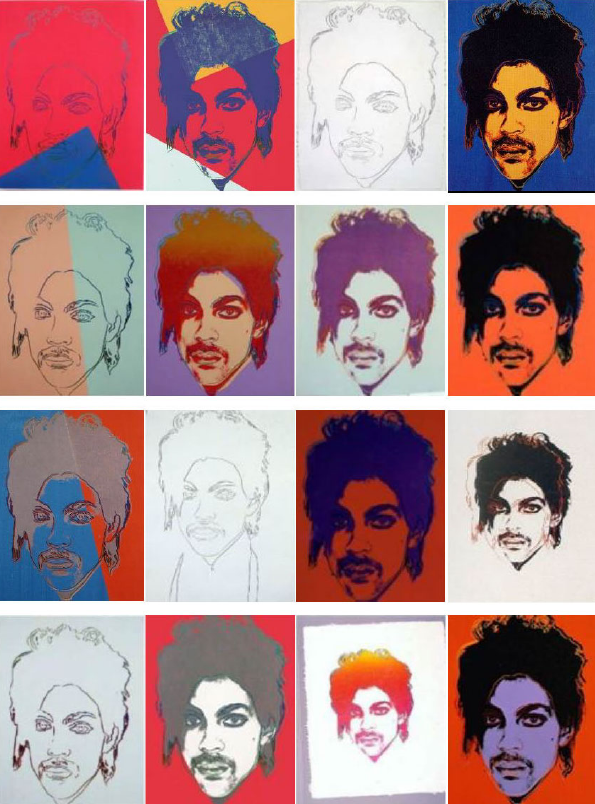

In 1984, Vanity Fair magazine commissioned artist Andy Warhol to create a portrait of the singer-songwriter sensation Prince. To assist Warhol in creating this art piece, the magazine paid Lynn Goldsmith, a well-known photographer in the rock-and-roll industry, $400 to license her photograph (the "Goldsmith Photograph") as an "artist reference." The Goldsmith Photograph, seen below on the left, was taken in 1981 for a Newsweek article when Prince was still an up-and-coming artist. Warhol created a series of 16 silkscreens and sketches (collectively known as the "Prince Series"), seen below on the right, by altering the Goldsmith Photograph in a variety of ways, including by cropping and colouring the photograph.

On the left is the 1981 black-and-white photograph taken by Lynn Goldstein, seen on page 4 of the decision. On the right are the 16 works that make up the Prince Series, included in the Appendix of the decision.

After Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair featured another one of the Prince Portraits, known as "Orange Prince." This was licenced by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts ("AWF"), to Vanity Fair's parent company, Condé Nast, without Goldsmith's permission. The AWF and Goldsmith then found themselves in court, battling over whether this amounted to copyright infringement. A lower court judge agreed with the AWF, finding that Warhol's work amounted to a "transformation" of the Goldsmith Photograph, therefore falling under the "fair use" exception to copyright infringement as it conveyed an entirely different meaning. According to the lower court, Goldsmith's permission was therefore not required in order for the AWF to licence the Prince Series to Vanity Fair. However, this was overturned on appeal. The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit found that Goldsmith's permission was, in fact, required to grant this licence because the Prince Series retained the "essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements."[1] The Court of Appeals also chided the lower court for acting as an "art critic" - by determining that the Prince Series conveyed a unique meaning. The matter was ultimately appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States ("SCOTUS") to decide whether the Prince Series amounted to a "transformation" of the Goldsmith Photograph and therefore fair use. In the highly anticipated decision on May 18, 2023, SCOTUS rendered its decision in which it found that the AWF was not entitled to rely on the fair use exception and so the use constituted copyright infringement.[2]

Fair use is a concept under United States copyright law that allows the unauthorized use of copyrighted work under certain circumstances. The fair use exception is similar to the Canadian concept of "fair dealing"; however, the application of fair use is broader than the list given in the US Copyright Act. The Canadian statutory concept is, in contrast, finite; it is limited to uses for the following purposes: education; satire; parody; research; private study; criticism; and news reporting.

There are four factors to consider when determining whether the use of a particular copyrighted work constitutes fair use. One of these factors considers the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for non-profit educational purposes. The central question in assessing this factor is whether the new work seeks to achieve the same purpose as the original, or whether it instead "adds something new, with a further purpose or different character."[3]

The sole question before SCOTUS was whether this fair use factor weighed in favour of the AWF. The AWF argued it did because the Prince Series was "transformative" as it conveyed a different meaning and message than the Goldsmith Photograph. Therefore, according to the AWF, the Prince Series sought to achieve a different purpose from the Goldsmith Photograph. SCOTUS did not agree.

Focusing largely on the commercial nature of the AWF's use of the Prince Series, the SCOTUS majority held that Warhol's transformation of the Goldsmith Photograph was not enough to tip the scales as "the degree of difference must be weighed against other considerations, like commercialism."[4] According to Justice Sotomayor, writing for the majority, "[a]lthough new expression, meaning, or message may be relevant to whether a copying use has a sufficiently distinct purpose or character, it is not, without more, dispositive of the first factor."[5] This decision arguably narrows the fair use concept closer to the Canadian fair dealing exception.

There are many groups and individuals who have criticized this decision, SCOTUS Justice Kagan being one of them. In a particularly scathing dissent, Justice Kagan said that:

"Inhibit[ing] subsequent writers" and artists from "improv[ing] upon prior works"—as the majority does today—will "frustrate the very ends sought to be attained" by copyright law. Harper & Row, 471 U. S., at 549. It will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.[6]

While we certainly hope that Justice Kagan's fears will not be realized, the implications of this decision could indeed be far reaching. They could impact the creation of NFTs, images created by AI image generators, and other uses in virtual environments. The argument that a defendant's use "transformed" the original copyrighted work is particularly attractive when copyrighted works are used in virtual environments, as the alleged infringement is typically an animated digitalized version of the original. In the case of AI image generators, as previously discussed here, although the image can be entirely "original," the technology is capable of generating images that bear striking resemblances to other known works. Creators working in these spaces should use caution when using works protected under US copyright laws, and should consider seeking legal advice before proceeding.

[1] The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, No. 19-2420 (2d Cir. 2021) at page 30.

[2] The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith et al. No. 21-869 (18 May 2023), online (pdf): Supreme Court of the United States < https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/21-869_87ad.pdf > (Warhol).

[3] Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music Inc., No. 92-1292 (7 March 1994), Supreme Court of the United States (WL).

[4] Warhol, at page 12.

[5] Warhol, at page 12.

[6] Warhol, at page 36.

NOT LEGAL ADVICE. Information made available on this website in any form is for information purposes only. It is not, and should not be taken as, legal advice. You should not rely on, or take or fail to take any action based upon this information. Never disregard professional legal advice or delay in seeking legal advice because of something you have read on this website. Gowling WLG professionals will be pleased to discuss resolutions to specific legal concerns you may have.