Jasvir Jootla

Partner

Article

17

This article was updated October 2024

On 5 October 2022, the Supreme Court handed down its decision in the case of BTI 2014 LLC v Sequana SA and others[1]. This is the first time that the Supreme Court has addressed the questions of whether there is a duty owed to creditors where a company may be at risk of insolvency, and the point at which that duty is triggered.

The decision raises important issues for company directors, with judges at the highest level commenting on their expectations of directors where a company is likely to face distress. We consider these comments and the issues which they now pose in our overview and Q&A below.

When does the creditor duty arise?

What is the scope of the creditor duty?

What does the creditor duty mean in practice?

Can members ratify acts of directors committed in breach of the creditor duty?

Can the creditor duty apply to a decision by the directors to pay a lawful dividend?

Does the creditor duty impact on other statutory duties of directors?

Does the creditor duty conflict with statutory provisions on wrongful trading and preferences?

Does the creditor duty conflict with the rules on transactions defrauding creditors?

What happens when the creditor duty is breached?

What should we take away from this judgment?

The judgment confirms that there are circumstances in which directors would need to consider the interests of the creditors to the company and this was described in the judgment as a "creditor duty". It forms part of the common law duty owed by the directors to the company, but it is not a free standing duty owed direct to creditors.

The creditor duty will be triggered when the directors know, or ought to know, that the company is insolvent or bordering on insolvency or that an insolvent liquidation or administration is probable.

It is worth noting that, although all five judges agreed on the outcome of the decision in Sequana, there are four distinct voices in the judgment that, in places contain some differences in reasoning. This is a case in point as only three of the Lords referenced the knowledge of directors as being part of the trigger.

What was clear however, is that the trigger is not based upon a company being at a "real risk" of insolvency, nor that the company is "likely" at some point in the future to become insolvent on either a cash flow or balance sheet basis. In handing down the judgment, Lord Briggs also commented that "it is not enough that insolvency itself from which the company may well recover is probable".

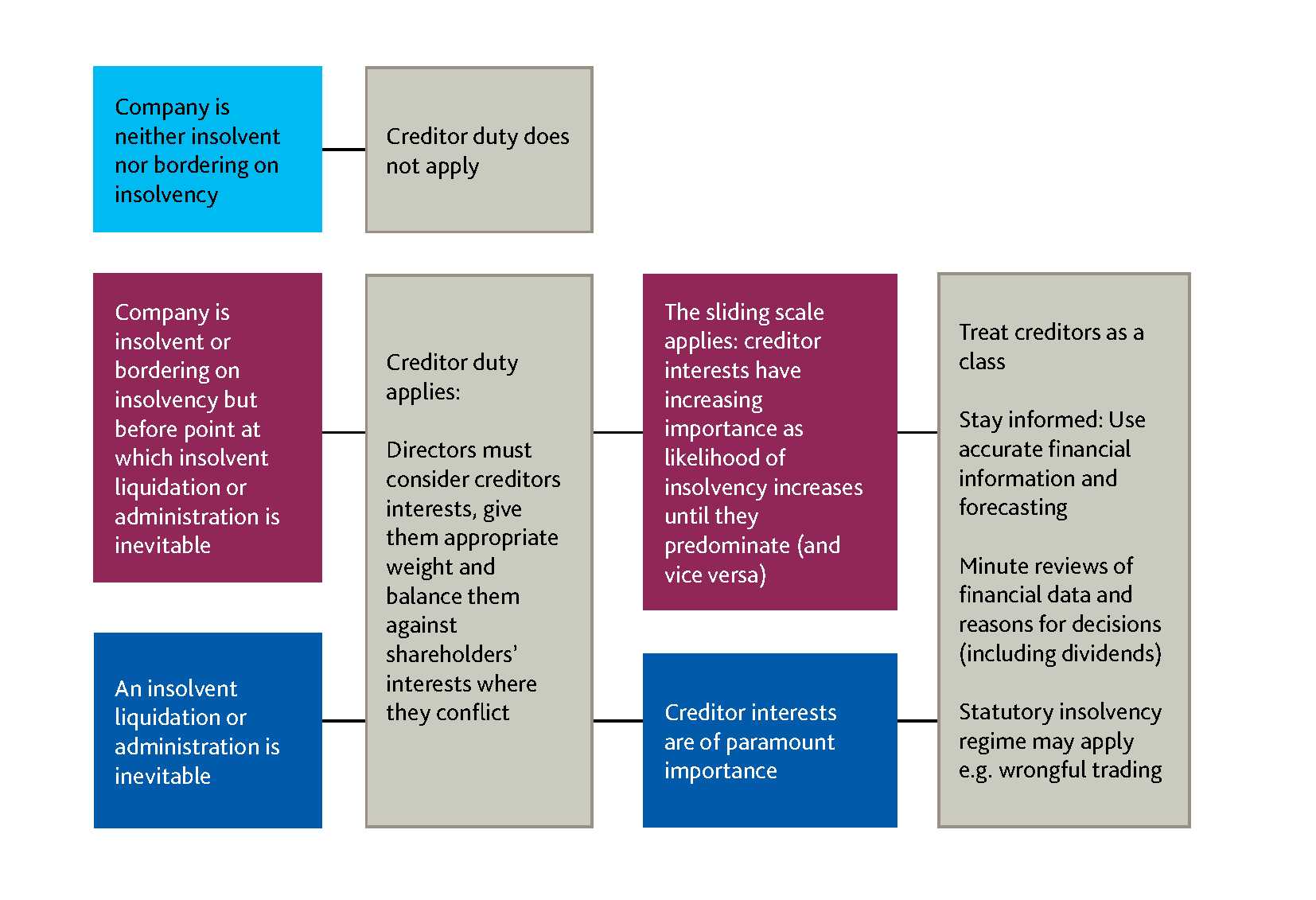

Directors should consider the scope of the creditor duty in the context of three stages of a company's life cycle:

1. Before a company is bordering on insolvency or is insolvent.

No creditor duty.

2. Where a company is insolvent or bordering on insolvency but prior to the time when insolvent liquidation or administration becomes inevitable.

At this point the creditor duty is triggered and directors have a duty to "consider creditors' interests, to give them appropriate weight, and to balance them against shareholders' interests where they may conflict"[2]

A sliding scale applies so that the interests of creditors assume an ever increasing importance among the company's stakeholders as the likelihood of insolvency increases until they predominate. Logically this scale could slide both ways, with the balance moving away from creditors should the threat diminish, and back again should it increase again.

3. Once the company is faced with an inevitable insolvent liquidation or administration.

At this point the interests of the creditors are paramount.

It was decided that the duty to creditors must be to treat the creditors as a class. This is partly because individual creditors may be in different positions and may even have conflicting interests. It also acknowledges the fact that the make-up of creditors as a body can change for so long as debts are being incurred and discharged.

Lady Arden's judgment went further and contains comments to the effect that directors do not need to consider separately the interests of creditors in a "special position" for example because they are subordinated or company liabilities to them are long term or contingent.[3] This is to be expected as it is consistent with the position under s214 Insolvency Act 1986 which requires the interests of all creditors as a body to be taken into account (including contingent and prospective creditors) once the duty to creditors becomes paramount.

Insolvency is determined according to the cash flow or balance sheet tests which will be familiar to directors and advisers alike. However directors will need to be more forensic in having accurate financial information and forecasting available to them at any given point to determine how close insolvency may be, in order to understand the extent to which they need to give more or less weight to the interests of creditors. This analysis, with reference to the financial data and forecasts would need to be available and considered at the relevant board meetings and recorded in the minutes.

Whilst it is useful to have clarification on the timing and description of the creditor duty, it is expected that there will be difficulties in applying the rule in practice.

It was unanimously agreed that the creditor duty had not been triggered in Sequana's case, which concerned the payment of a dividend by a solvent company. However it will be harder to apply to companies moving along the sliding scale.

There is an acknowledgement in the judgment[4] that there have been plenty of authorities on the existence of a creditor duty but this has not been matched by unanimity on content. Instead it recognises that it is "likely to be a fact sensitive question" and that the rule of law "has yet to be finally fleshed out". Given that there are also comments noting the practical difficulties that will arise as a result of the requirement placed on directors in this situation and an acknowledgment "decisions must be taken immediately" by directors, it is hoped that the courts will take a balanced approach to directors who can demonstrate that they have weighed up the interests of creditors as part of their decision-making process, even if a rescue is ultimately impossible. However, it is expected that we will see further litigation in this area as the common law rule is developed against the backdrop of the statutory insolvency regime.

For these reasons it is recommended that, once the creditor duty is engaged, directors should pay close attention to their financial data and forecasts, and document the reasons for their decisions affecting creditors in order to record:

Directors may face challenges by shareholders who disagree with the directors on the extent to which creditors interests are weighted. The directors will need to meet any such challenges with the financial information to support their decisions.

Three of the Lords held the view that the creditor duty would be triggered by a state of affairs that the directors know or "ought to know". Lady Arden did not express this view but commented that:

Taken together, this appears to be a firm warning that directors must keep themselves informed.

No. There is a recognised qualification to the Duomatic principle[6] that the shareholders cannot ratify or authorise a transaction which would jeopardise the company's solvency or cause loss to its creditors. Lord Briggs commented[7] that the trigger for engagement of the creditor duty coincides with the moment that ratification ceases to be available.

Yes. The creditor duty could be engaged even if the proper process is followed for the approval and payment of a dividend. The judgment of Lord Briggs gives two reasons for this[8]:

Once triggered, the creditor duty modifies the statutory duty of directors in Section 172(1) Companies Act 2006 to act in the way that they consider, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole. This was considered to be in keeping with the provision of s172(3) of that Act which acknowledges that the duty under s172(1) is "subject to any enactment or rule of law requiring directors, in certain circumstances, to consider or act in the interests of creditors of the company".

The other duties referred to in sections 171 - 177 Companies Act 2006 are not expressed to be subject to the qualification found in s172(3). However, the other duties were equally considered not to give rise to such likelihood of conflict and so could co-exist with the creditor duty.

No. It was found that there was no conflict between the creditor duty and the wrongful trading and preference provisions found in section 214 and 239 Insolvency Act 1986. Those continue to apply and directors must continue take them into account when taking decisions affecting an insolvent company.

In an earlier hearing, the dividend payment made by Sequana was found to be a breach of Section 423 Insolvency Act 1986, as a transaction defrauding creditors. However, despite this, the payment was not found to be a breach of the creditor duty. Lord Briggs noted that "it is, in passing an irony in the present case that the May dividend has been found to have offended section 423 but no claim that it involved for that reason alone a breach of duty by the respondent directors has ever been pursued."[9] Directors should be aware that causing the company to enter into transactions which are open to review in a subsequent insolvency may in some, if not all, cases amount to a breach of duty on their part.

On 11 June 2024, the High Court handed down its decision in the case of BHS Group Ltd and other companies (all in liquidation) Chandler v Wright ([2024] EWHC 1417 (Ch)). This is the first time that the court has applied the creditor duty established in Sequana.

The decision emphasises important considerations for the board of directors of distressed companies in the context of discharging the creditor duty, and also introduces a novel concept of a "misfeasant/misfeasance trading" claim.

Misfeasant trading is a separate claim to wrongful trading. The main difference is that while a wrongful trading claim can arise when directors know, or ought to know, that there is no reasonable prospect of avoiding an insolvent administration or liquidation, the misfeasant trading claim can arise at an earlier point, i.e. from the point the creditor duty is engaged (see "The sliding scale" section above).

This means that insolvent liquidation or administration do not have to be inevitable for a misfeasant trading claim to arise. It is sufficient that insolvency is only probable for the purposes of misfeasant trading.

The court also clarified that an "insolvency-deepening activity" can amount to a breach of duty by directors, even though insolvent liquidation or administration is not inevitable and there is no liability for wrongful trading. Such an activity may, depending on the circumstances, include entering into onerous and/or expensive finance transactions when the creditor duty has arisen and directors should have properly considered the interests of creditors.

This development not only opens up an additional claim against directors where their conduct in the lead up to insolvency is judged from an earlier "trigger date", but also means that, potentially, even outside of an insolvency, disgruntled creditors may look to directors' conduct and seek to understand if they have claims against the director (although this is likely to be used more as a threat than used in reality).

If a misfeasance claim is successful, the directors may be held personally liable and the court may order them to contribute to the assets of the company for the benefit of its creditors.

The decision highlights the importance of directors staying informed and assessing the company's financial position continually, alongside their directors' duties (including the creditor duty). It also reiterates the significance of obtaining professional advice and keeping a clear record of the board's decision-making process.

It is positive that the judgment provides clarification on when directors will be required to consider creditors' interests and the ability of directors to apply a sliding scale to the balancing act between the potentially competing interests of creditors and shareholders once the company insolvent or is bordering on insolvency. However, the balancing exercise could be difficult to interpret in practice and directors are advised to tread cautiously in order to avoid being one of the test cases which are expected will be required in order to flesh out the detail of how the sliding scale will be applied by the courts.

We can take away the following:

Should you wish to discuss any of the points raised in this article, please contact Jasvir Jootla, Tom Pringle, Karolina Lewandowska, or Cat Naylor.

Footnotes:

[1] [2022] UKSC 25

[2] Per Lord Briggs at para [176]

[3] At para [256]

[4] Per Lady Arden at paras [250] and [448]

[5] At para [304]

[6] From Ciban Management Corp v Citco (BVI Limited) [2020] UKPC 21; [2021] ACC 122

[7] At para [196]

[8] At paras [160] - [162]

[9] Para [182]

CECI NE CONSTITUE PAS UN AVIS JURIDIQUE. L'information qui est présentée dans le site Web sous quelque forme que ce soit est fournie à titre informatif uniquement. Elle ne constitue pas un avis juridique et ne devrait pas être interprétée comme tel. Aucun utilisateur ne devrait prendre ou négliger de prendre des décisions en se fiant uniquement à ces renseignements, ni ignorer les conseils juridiques d'un professionnel ou tarder à consulter un professionnel sur la base de ce qu'il a lu dans ce site Web. Les professionnels de Gowling WLG seront heureux de discuter avec l'utilisateur des différentes options possibles concernant certaines questions juridiques précises.