John Coldham

Partner

Head of Brands and Designs (UK)

Co-leader of Retail & Leisure Sector (UK)

Article

13

The Supreme Court has today (9 March) handed down its judgment, unanimously upholding the Court of Appeal's decision: PMS did not infringe Trunki's registered design. This article offers practical guidance on what the decision means for designers, and also looks at the judgment itself in detail.

Almost exactly two years ago, on 28 February 2014, the Court of Appeal overturned the High Court's decision that PMS International had infringed a Community Registered Design belonging to Magmatic, which trades under the name Trunki. The High Court's decision that PMS had also infringed certain unregistered designs was not appealed.

What concerned designers, however, was the basis on which the Community Registered Design claim was rejected. As a result, the decision to allow an appeal to the Supreme Court was welcomed, so that the highest court in the land could give guidance on how registered designs should be interpreted and, therefore, filed in the first place.

On 9 March 2016, the Supreme Court handed down its judgment, unanimously upholding the Court of Appeal's decision: PMS did not infringe Trunki's registered design. While the Supreme Court noted that the Trunki design was "both original and clever", and stated that it is "with some regret" that the decision has gone against Trunki, this appeal was not concerned with an idea or an invention, but with a design.

This article offers practical guidance on what the decision means for designers, and also looks at the judgment itself in detail.

Trunki is a British success story; from humble beginnings in around 2003, by 2011 Trunki estimates that approximately 20% of all 3-6 year olds in the UK possessed a Trunki. By 2014 the award-winning product was sold in 97 different countries.

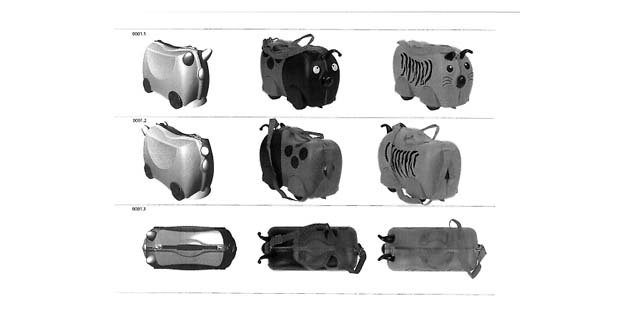

Designer Rob Law founded his company in 2003, and registered his first Community Registered Design the same year. In 2012, the managing director of PMS saw the Trunki product while travelling, recognised its qualities and decided to create a discount version. This resulted in the launch of the Kiddee Case, which sold in two basic versions - an animal version with handles formed to look like ears, and an insect version with handles formed to look like antennae. These were then decorated to create a variety of models including a tiger and a ladybird.

The main decision to be made by the Supreme Court was how a registered design should be interpreted. This is of most interest to designers as it should affect how they file their own designs in future. Here is a summary of the key guidance that the Supreme Court gave designers in brief, and we will explore the reasons in more detail below.

Our simple message to designers is that, regardless of the fact that the Supreme Court has decided against Trunki, registered designs are still a powerful tool against infringers.

Although UK unregistered designs tend to be more successful at court (as seen by Trunki itself at first instance), partly because they are limited to shape and as such are generally broader, this does not tell the full story. Unregistered rights require the claimant to prove copying, and to prove ownership and subsistence. With a registered design, none of this is required.

The lesson from the Supreme Court, however, is that utmost care should be taken when filing registered designs. Any detail that is included in the design could be used to restrict its scope, and so great care should be taken to keep the designs as simple as possible (while bearing in mind the possible prior art, and ensuring that the design is still valid over it).

Designers should also consider using the system to their advantage; registered designs are cheap in comparison to any other registered IP right, and there are discounts for multiple filings on the same application as set out above. Therefore, designers should consider registering their more key products in more than one way - perhaps registering parts of the product, and perhaps in more than one format, such as a line drawing as well as a fully rendered CAD.

It remains to be seen precisely how designers will make it clear whether they intend to claim an absence of ornamentation as a feature of the design or not; the Supreme Court did not offer any particularly practical guidance on this (as it said that it is not its role to do so), and we hope that the UK Intellectual Property Office, or OHIM, will do so as part of updated guidance on how best to file designs in light of this case. In the meantime, it is likely that a vast number of existing designs on the register will be narrower than those filing them originally envisaged, particularly those that were filed as photographs or detailed CAD drawings.

It is clear from Art 3 of the Community Designs Regulation (6/2002) that a design means the appearance of the whole or part of a product resulting from the features of, "in particular, the lines, contours, colours, shape, texture and/or materials of the product itself and/or its ornamentation". The use of "and/or" means that you could have a registered design that is just one of those features, such as shape alone. The Supreme Court has confirmed that this approach is correct.

Once this premise is accepted, the question becomes clearer: how do designers who want to file a registered design that solely protects shape make it clear that this is what they want to do? They cannot include a verbal disclaimer, or description, as these are precluded by the Regulation (Art 36(3)).

In the earlier case of Proctor & Gamble v Reckitt Benckiser, the claimant argued that, in light of the registration, only product shapes should be compared. The Court of Appeal agreed, saying that the registration was "evidently for a shape". The registered design (for an air freshener aerosol) was a series of line drawings in monochrome, and as such it was taken to be shape only.

However, in the later case of Samsung Electronics v Apple, a case about a registered design for a tablet computer (similar, but not identical, to Apple's later iPad design), the Court of Appeal found that the design was not for shape alone. In that case, the Court of Appeal noted that Apple had contended (without objection from Samsung) that it was a feature of the registered design that it had no ornamentation - that is, although the design was a monochrome line drawing, it protected more than simply the shape, as it was a feature that it had an absence of other features.

So you have two cases with the same style of registered design - a monochrome line drawing with limited other ornamentation, and they are being interpreted apparently differently; P&G's design is taken to cover any ornamentation as it is simply for shape, and Apple's design is interpreted as covering the shape and the fact that it has no ornamentation. It follows that the level of surface decoration on the Samsung alleged infringement was relevant, whereas it was not relevant in Reckitt Benckiser's product.

The Supreme Court considered these cases, but then addressed the question of how the Trunki registered design should be interpreted. It was not registered as a simple line drawing, but rather rendered CAD drawings - three dimensional images which show the suitcase from different perspectives and angles and show the effect of light upon its surfaces.

The Supreme Court agreed with the Court of Appeal's description of the design as "looking like a horned animal with a nose and a tail", and it does so "both because of its shape and because its flanks and front are not adorned with any other imagery which counteracts or interferes with the impression that the shape creates".

The Supreme Court went on to agree with the Court of Appeal that the existence of contrasting colours in the registered design (for example, the wheels were black, unlike most of the rest of the representation) was in itself something that should be taken into account. The registration covered any colour, but the colour contrast itself was relevant.

As summarised by the Supreme Court, this means that there were three criticisms of the trial judge's approach by the Court of Appeal, and the Supreme Court agreed with those criticisms:

Summarising the role of the appellate court, the Supreme Court said that, as the Court of Appeal's approach was correct, the Supreme Court should be "very slow indeed to interfere with their conclusion", even if it had felt that it might have come to a different conclusion. As a result, it did not do so, although it noted that it would have come to the same result as the Court of Appeal in any event.

Finally, the Supreme Court rejected the suggestion from Trunki and the Comptroller of Patents (who intervened in the case) that there was a point that should be referred to the European Court - the CJEU, particularly on whether (and how) the lack of ornamentation should be a feature in its own right.

The Supreme Court said that the question of how designs should be interpreted can be gleaned from the Regulation, and the practice of OHIM, and it found that the suggestion that the lack of ornamentation cannot be a feature in its own right is unarguable, and it would be "extraordinary" if it was right, so the question did not need to be referred.

The images of Trunki's design, next to the two PMS products that were the subject of the case:

NOT LEGAL ADVICE. Information made available on this website in any form is for information purposes only. It is not, and should not be taken as, legal advice. You should not rely on, or take or fail to take any action based upon this information. Never disregard professional legal advice or delay in seeking legal advice because of something you have read on this website. Gowling WLG professionals will be pleased to discuss resolutions to specific legal concerns you may have.