Vivian Desmonts

Partner

Co-Managing Partner of China Practice

Article

26

Authored by Natalia Thawe and Anita Nador, with contributions by Matt Hervey (UK), Alexis Augustin (France), Vivian Wei Cheng* (Singapore) and Vivian Desmonts (China).

*Vivian Wei Cheng is a patent attorney working in the office of JurisAsia LLC with who Gowling WLG has an exclusive association.

What is know-how? What is a trade secret? Is all know-how a trade secret? Is all know-how confidential? How do these terms fit into the larger proprietary information framework that we refer to as intellectual property (IP)?

The terms confidential information, trade secrets, and know-how are commonly – and erroneously - used interchangeably. For businesses, this frequently results in confusion and, just as often, missed opportunities to optimize the full value of IP assets. Indeed, understanding how these terms are defined, where they overlap, and how each is treated in law, is a critical first step for organizations looking to identify, protect, and valuate their intangible assets – ideally as part of a comprehensive IP strategy. Although the exact definitions for agreement purposes may be tailored to the specific industry/business, the general concepts are as follows:

So understanding the distinction between "confidential information", "trade secrets" and "know-how", and how one labels and handles different types of information is important in the valuation assessment process of a business or technology. This can be explained at the most basic level by the economic model of supply and demand. If there is only one company that knows how to make or can sell a widget in a particular time, for a particular cost, of a particular quality, and/or for a particular purpose, or provide a particular service, versus two companies, versus ten companies, etc… and there is a demand for same, then that often correlates to the potential value of the information. The degree of effort to obtain said information/knowledge also is factored in.

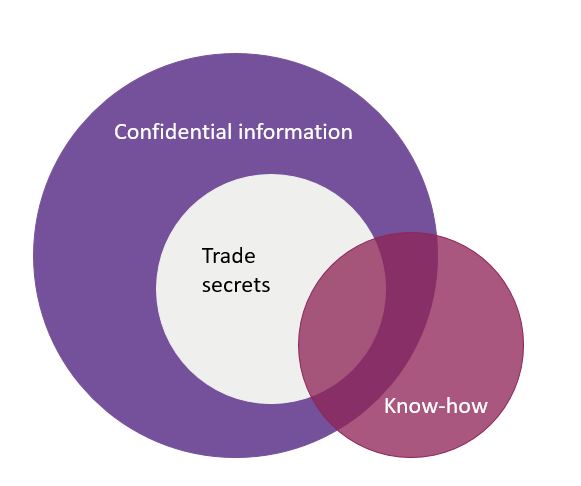

Figure 1 - How do they fit together?

By way of illustration, it can be seen in Figure 1 that while all trade secrets, by their nature, comprise confidential information, confidential information with no commercial or strategic value isn't deemed a trade secret. In a similar way, trade secrets may comprise know-how, but not all know-how qualifies as a trade secret. Further, confidential information that may not be a trade secret, may still have value as know-how or have other aspects that may be valuable depending on the context, and as noted above, know-how may still have value if it is not confidential.

Clearly, the intersections between these three terms can lead to some blurred lines and circular definitions. This becomes particularly problematic in the context of legal agreements and company policies. Not only can this ambiguity directly impact adherence to such documents, but it also throws their enforceability into question. In the cases noted below, it can be seen that context matters. We would strongly encourage taking time to define the terms in light of the subject matter and activities of the agreement.

Accordingly, the restrictions in agreements must be appropriate to the sensitivity of the information, and that information, in turn, must be clearly identified and correctly classified for a successful enforcement. For instance, the extent to which a trade secret can be protected may be significantly greater than general know-how: an ex-employee may be prevented from using an important trade secret but is, typically, free to use non-confidential know-how (that is not secret and for instance, that may be seen by a court to be general skills of the trade or general industry knowledge).

Over the years, courts have provided some guidance on how these overlapping terms may be used and distinguished in different contexts. As the examples below illustrate, the common theme established through the case law is that confidential information – whether trade secret, know-how, both or neither – must be identified with some specificity.

The distinction between what was know-how and what was a trade secret was examined in United States Court of Appeal decision, Mallet and Company Inc. v. Lacayo.[2] In this case, the court was ultimately unable to determine which of the disputed information qualified as a trade secret and, as a result, the plaintiff's likelihood of success in establishing trade secret misappropriation.[3] Consequently, the court highlighted that owners of trade secrets must identify their trade secrets with some specificity, which is a context-specific matter, and that they should be distinguishable from an employee's general know-how.[4] The court also held that employers can freely identify and protect their specific proprietary information (e.g. employer know-how), recognizing that the line distinguishing between an employee's general knowledge or skill and an employer's trade secrets "may often be difficult to draw."[5] The decision emphasized that owners of trade secrets carry the burden of demonstrating that certain information is protectable and "not general industry knowledge".[6]

In Skycope Technolgies Inc. v Jia,[7] the British Columbia Supreme Court in Canada similarly emphasized the importance of precisely identifying what information, and what know-how, is considered confidential. The court clarified that confidential information "must be inaccessible, have a quality of originality or uniqueness, and must not be in the nature of "know-how"." Although, at first glance, the court appears to exclude know-how from the definition of "confidential information", the court clarifies that some know-how may be confidential and must also be precisely identified to be protected. As an example, the court states, "information that is readily obtainable from a known source is not confidential; however, if using it saved a defendant the substantial time, effort and expense that would otherwise have taken to obtain it, it may be confidential."[8]

The court in Skycope ultimately held that, apart from the plaintiff's source code and market research, the plaintiff's confidentiality claims over several other categories of information, including research and development know-how, were unsuccessful, citing unsupported evidence and failure to specify with precision what information was alleged to be confidential.[9]

In Canada, a 2022 Ontario Superior Court decision addressing the licensing of know-how, 7868073 Canada Ltd. v. 1841978 Ontario Inc,[10] highlighted that the importance of defining confidential know-how with precision is directly linked to its commercial value, if any. Addressing the key issues at play in 7868073 Canada Ltd. v. 1841978 Ontario Inc, the court explained that "know-how" has been described "as any useful commercial information that is not protected by a patent and that is known to the liscensor [sic] but not the licensee" and that "a licensor's right to control the use of know-how is limited to the extent to which the information can be protected as confidential information."[11] The decision attempts to clarify that the value of know-how may be driven by the degree to which that know-how is confidential or not generally known to the public. This, in turn, renders the know-how potentially licensable and able to be commercialized.

UK law also recognises the overlaps and distinctions between confidential information, trade secrets and know-how (and private information under human rights law).[12] Long-established equitable rights in confidential information were supplemented in 2018 by the EU's harmonised law on trade secrets.[13] In accordance with the harmonised law, a trade secret, unlike confidential information, must by definition have commercial value because it is secret and must be "subject to reasonable steps under the circumstances, by the person lawfully in control of the information, to keep it secret".[14]

As in the US and Canada, in the UK it is important to distinguish in contract and in enforcement actions confidential information (whether or not a trade secret) sufficiently valuable to justify post-employment restrictions from more general business information and know-how.[15]

French law provides mechanisms for the protection of confidential information and offers examples of information that is legally deemed confidential,[16] but it does not specify what confidential information is. Therefore, the confidential nature of information depends on the sovereign judgement of the French courts or on contractual provisions if they exist. However, a detailed analysis of the case law shows that the French courts tend to consider as confidential information which (i) is not generally known or easily accessible, and (ii) has actual or potential commercial value.[17]

Know-how has been protected in France for many years;[18] however, until recently, it had no legal definition. It was only in 2004 that the EU Commission Regulation No 772/2004 of 27 April 2004, which is directly applicable in France, provided the first definition of know-how. Regulation No 772/2004 has since been replaced by the EU Commission Regulation No 316/2014 of 21 March 2014, which provides a broader definition of know-how[19] compared to the one given by the Regulation No 772/2004.

Pursuant to its Article 1 of Regulation No. 316/2014, know-how is defined as a package of practical information resulting from experience and testing, which must meet three criteria. It must be:

These criteria have since been regularly reiterated by case law, even though French courts sometimes use some different wording.[20]

Finally, trade secrets, similar to know-how, have been protected under French law for many years.[21] However, it wasn't until 2018 that Law No. 2018-670,[22] which transposed the EU Directive 2016/943 of 8 June 2016, provided a clear definition of trade secrets. Since then, pursuant to Article L.151-1 of the French Commerce Code, any information is protected as a trade secret if it (i) is not generally known or easily accessible, (ii) has actual or potential commercial value by virtue of its secrecy, and (iii) is the subject of reasonable protective measures by its legitimate holder to maintain its secrecy.

Therefore, it is evident from the above that confidential information, know-how and trade secrets are different concepts. In line with other countries, trade secrets are a specific type of confidential information, those that are the subject of reasonable protective measures by its legitimate holder to maintain its secrecy. Under French law, know-how is another type of confidential information since all information covered by know-how must meet the conditions to be considered as confidential. Therefore, know-how covers confidential information which is practical information, resulting from experience and testing. Finally, despite the clear differences between these concepts, know-how and trade secrets can still overlap under French law, depending on the context and facts, as an information item may fall into either of these two categories.

In Singapore, trade secrets are generally regarded as a subset of confidential information and are protected primarily through the law of confidence. To claim breach of confidence in Singapore courts, the information must have "the necessary quality of confidence about it" and must have been "imparted in circumstances importing an obligation of confidence".[23]

In Clearlab SG Pte Ltd v Ting Chong Chai[24] ("Clearlab"), it was stated that "mere confidential information" (i.e., confidential information of a lesser degree of confidentiality than trade secrets) is different from "trade secrets". In other words, trade secrets are regarded as having a higher level of confidentiality than "mere confidential information". Clearlab further states that the confidentiality requirement of "confidential information" is satisfied if the information is relatively inaccessible to the public, i.e., it has not become public knowledge.

The judge in Clearlab also referred to Faccenda Chicken Ltd v Fowler[25] ("Faccenda") and stated that an express covenant is not capable of restraining an ex-employee from using confidential information which falls short of a trade secret. Thus Clearlab could not protect its mere confidential information (as opposed to trade secrets) from further use or disclosure by the ex-employees.

The judge in Clearlab also took care to distinguish between "skill and knowledge" belonging to an ex-employee and "confidential information" belonging to the ex-employer. It was held that, while an ex-employer's confidential information should be protected, the scope of protection should not unreasonably encroach upon the ex-employee's ability to utilise their skill and knowledge to compete with the ex-employer or to seek alternative employment in the same field. By "skill and knowledge" the judge referred to Faccenda and described the same as "which once learned necessarily remains in the servant's head and becomes part of his skill and knowledge applied in the course of his master's business".

China is a continental law jurisdiction and the legal definition of trade secret is codified in the Anti-Unfair Competition Law (revised in 2019). The law states that a trade secret refers to technical information or operational information that are not known to the public, can be used to bring economic benefits to the right holders, have practicability and for which the right holders have taken measures to ensure confidentiality.

In China's case law, the People's Courts will indeed focus on the following three aspects when judging whether a trade secret should be legally protected: (1) it is confidential information; (2) it has commercial value; and (3) the right holder has adopted measures to ensure confidentiality.

Taking clients' information as an example, in the case of Huayang New Technology (Tianjin) Group Co., Ltd ("Huayang"). v. Machdarecare (Tianjin) Technology Co., Ltd.,[26] the Supreme People's Court of China ("SPC") held that basic client information in Huayang's client list were actually easily available to the public through simple internet searches. In this case, the client list only contained routine transactional information, such as clients' names, contact details, order dates, quantities and specifications of goods. It did not contain in-depth details such as clients' transaction habits or their intentions to purchase, which would have had potential commercial value. Although Huayang had taken measures to ensure the confidentiality of its client list, the SPC ruled that the client list did not constitute a trade secret protected under the Anti-Unfair Competition Law.

However, in the case of Lumi Legend Corporation ("Lumi"). v. Wu Tianci et al.,[27] the People's Court did regard Lumi's client list as a trade secret. This is because that clients list included not only general transactional information, such as clients' names and contact details, but also information reflecting clients' trading habits and preferences, such as payment terms, packaging requirements, purchasing/selling prices, which the court considered as having potential commercial value.

When dealing with know-how, knowledge and skills acquired by employees through their employment relationship, the SPC has indicated its position in the above-mentioned case of Huayang: the knowledge, experience and skills acquired and accumulated by employees during their work constitute the foundation of their survival and work capacity. The SPC held that the freedom to autonomously utilize these resources shall be granted to employees after they leave their position, except if the know-how can be recognised as the employer's trade secrets.

Besides, the SPC will generally not apply the legal protection of trade secrets or recognise any improper means of a former employee conducting business, when a customer conducts transactions with a former employee's new employer, trusts the employee as an individual and the customer voluntarily chooses to conduct transactions with that individual and his/her new employer (re. the Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Civil Cases of Trade Secret Infringement published in 2020).

In any case, concluding robust NDAs or non-Disclosure, non-use and non-Circumvention agreements with business partners and/or employees is key for protecting confidential information in China.

Despite the confusion surrounding these terms, the solution for most organizations boils down to taking reasonable efforts to identify, protect, and valuate proprietary information. For those unsure of where to begin, an intellectual property professional can walk you through the steps, helping you a) determine which types of information are protectable and b) implement strategies to manage, commercialize and enforce your valuable information assets (see below the steps for a effect trade secrets management)).

Ready to begin a conversation? Learn more about Gowling WLG's trade secrets services.

Audit

Create

Implement

Monitoring and enforcement

[1] Criminal Code, RSC, 1985, c C-46, s 391(5); Uniform Trade Secrets Act at §1; Directive (EU) 2016/943 on the protection of undisclosed know-how and business information (trade secrets) against their unlawful acquisition, use and disclosure at Article 2(1); Anti-Unfair Competition Law of the People's Republic of China (revised in 2019) at Article 9; Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), Article 39.

[2] Mallet and Company Inc. v. Lacayo, 16 F.4th 364, (3d Cir. 2021). [Mallet]

[3] Mallet at 385-386.

[4] Mallet at 386-388.

[5] Mallet at 387.

[6] Mallet at 387.

[7] Skycope Technologies Inc. v Jia, 2023 BCSC 1288. [Skycope]

[9] While the plaintiff accepted that the research and development know-how in the field residing with the defendants before joining the company was not confidential, it alleged that the defendants did not have know-how relating to "wireless anti-drone technology" until they joined and therefore, such information was confidential. The court disagreed and held that know-how relating to general "wireless anti-drone technology" without any precision was too broad and not confidential (Skycope at paras 129-134, 141).

[10] 7868073 Canada Ltd. v. 1841978 Ontario Inc., 2022 ONSC 4557. [7868073 Canada Ltd]

[11] 7868073 Canada Ltd at paras 169-171; H. Roger Hart and Daniel R. Bereskin, (2007) "The Licensing and Commercializing of Intellectual Property" at 2-3.

[12] Human Rights Act 1998; misuse of private information was recognized as a separate tort in Vidal-Hall v Google Inc [2015] EWCA Civ 311.

[13] Directive 2016/943 on the protection of undisclosed know-how and business information (trade secrets) against their unlawful acquisition, use and disclosure (Trade Secrets Directive) [2016] OJ L157/1, implemented by the Trade Secrets (Enforcement, etc.) Regulations 2018 and retained after leaving the EU.

[14] Trade Secrets Directive, Article 2(1).

[15] E.g. Faccenda Chicken Ltd v Fowler [1986] ICR 297.

[16] For example, information provided in connection with the exercise of work councils' alert right (Article L.2323-54 of the French Labour Code), information relating to manufacturing processes (Article L.2315-3 of the same code), and the business reports which must be made provided internally pursuant to Article L.2323-13 of the same code are legally deemed to be confidential.

[17] Amiens Court of Appeal, 9 May 2007, 0600905; Paris Court of Appeal, 13 May 1997, XP130597X; Grenoble Court of Appeal, 26 September 2019, 17/03827, Paris Court of Appeal, 8 November 2017, 16/14658.

[18] French Supreme Court, 13 July 1966 and before that Aix-en-Provence Court of Appeal 23 April 1964.

[19] The EU Commission Regulation No 772/2004 of 27 April 2004 specified that know-how can be a non-patented information, which has been abandoned by the drafters of the EU Commission Regulation No 316/2014 of 21 March 2014.

[20] Paris First instance court, 2 March 2023, 19/07532; Lyon Court of Appeal, 10 November 2022, 19/03383; Versailles Court of Appeal, 10 February 2022, 20/03403.

[21] French Supreme Court, 9 Jun 1980, 78-15.100.

[22] Entered into force on 30 July 2018.

[23] I-Admin (Singapore) Pte Ltd v Hong Ying Ting and others [2020] SGCA 32, citing Coco v AN Clark (Engineers) Ltd [1969] RPC 41 ("Coco").

[24] Clearlab SG Pte Ltd v Ting Chong Chai [2014] SGHC 221.

[25] Faccenda Chicken Ltd v Fowler and others [1987] 1 Ch 117.

[26] Huayang New Technology (Tianjin) Group Co., Ltd("Huayang"). v. Machdarecare (Tianjin) Technology Co., Ltd [2019] No. 268 SPC Civil Retrial.

[27] Lumi Legend Corporation("Lumi"). v. Wu Tianci et al [2023] No.1470 Zhe 02 Civil Final Trial.

NOT LEGAL ADVICE. Information made available on this website in any form is for information purposes only. It is not, and should not be taken as, legal advice. You should not rely on, or take or fail to take any action based upon this information. Never disregard professional legal advice or delay in seeking legal advice because of something you have read on this website. Gowling WLG professionals will be pleased to discuss resolutions to specific legal concerns you may have.