Mikail Osman

Associate

Article

12

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 ("IRA") is the most significant legislative action taken by the United States ("US") to address climate change and promote the purchase of clean vehicles.

One of the most significant changes under the IRA is to amend the clean vehicle tax credit under Section 30D of the Internal Revenue Code ("IRC"). The amendments to section 30D, along with the proposed regulations and guidance, tighten restrictions on what are termed "foreign entity of concern" or "FEOC's" in the North American supply chain for clean vehicles, and mandate greater localization of the clean vehicle supply chain within North America and with trusted trading partners.

In this article, we explore how businesses located in Canada may be uniquely positioned to benefit from the IRA and expand their footprint in the US clean vehicle market.

The IRA allocates approximately US$370 billion for climate-related solutions, primarily in the form of some two dozen tax incentives to accelerate private sector investment in clean energy technologies.[1] Section 30D of the IRC, as amended by the IRA, provides up to a US$7,500 tax credit to purchasers of a "new clean vehicle" at the time of purchase. This credit is divided into two parts:

The critical mineral requirements apply to the applicable critical minerals contained in the battery from which the electric motor of a clean vehicle draws electricity. Under the critical mineral requirements, a minimum percentage of the value of such critical minerals in the battery must be either:

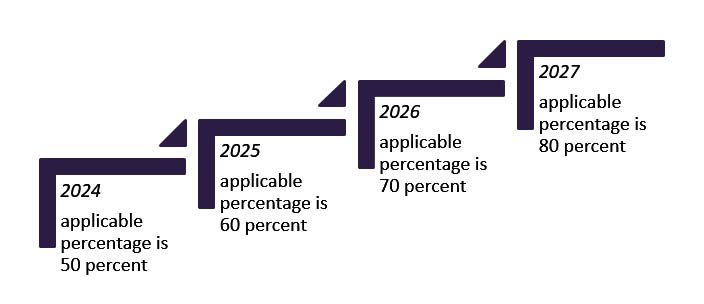

The applicable percentage for 2024 is 50 per cent. After 2024, this percentage increases by 10 per cent annually up to 80 per cent after 2026 (see Figure 1). [3]

A three-step process has been proposed for determining the percentage of the value of applicable critical minerals in a battery:

The emphasis on sourcing, processing and recycling critical minerals inside of North America may give Canadian-incorporated businesses preferential access to the US clean vehicle market and the benefits of the IRA.

Figure 1: The increasing percentage of the critical mineral requirements that must be sourced or processed in the US or countries with a free trade agreement with the US, or recycled in North America from 2024-2027

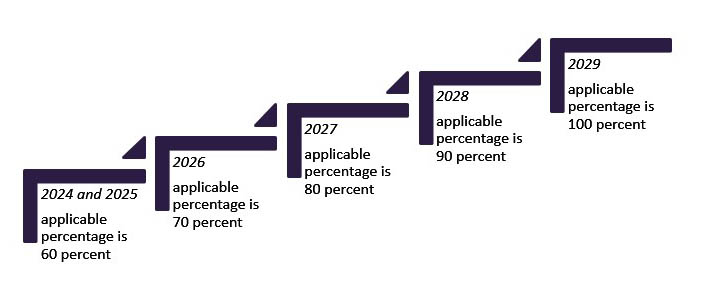

Under the battery component requirements, a minimum percentage of the value of the components contained in such a battery must be manufactured or assembled in North America. The applicable percentage for 2024 and 2025 is 60 per cent and increases by 10 per cent annually up to 100 per cent by 2029 (see Figure 2). [5]

A four-step compliance process has been proposed for determining the percentage of the value of the battery components:

The emphasis on manufacturing or assembling battery components in North America again reflects an intention to reduce reliance on supply chains outside Canada, the US and Mexico.

Figure 2: The increasing percentage of the battery component requirements that must be manufactured or assembled in North America from 2024-2029

The IRA aims to enforce measures that restrict an FEOC from gaining access to the US clean vehicle market. An FEOC includes "a foreign entity … owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a government of a foreign country that is a covered nation".[7] A "covered nation" is defined as China, Iran, North Korea and Russia.

Late last year, the Department of the Treasury issued a series of proposed regulations and the Department of Energy published guidance ("Proposed Rules") clarifying the meaning of an FEOC, proposing expansive meanings for each of the terms "foreign entity", "government of a foreign country", "subject to the jurisdiction" and "owned by, controlled by, or subject to the direction". [8]

A "foreign entity", for example, is proposed to include:

Under the proposed definitions, a foreign entity is deemed to be an FEOC under any of the following scenarios:[10]

In general, to qualify for the new clean vehicle tax credit, a vehicle placed in service after 2023 cannot contain battery components that were manufactured or assembled by an FEOC, and a vehicle place in service after 2024 cannot contain critical minerals that were extracted, processed or recycled by an FEOC.

Crucially, determining whether an entity is an FEOC requires careful analysis of its legal nature, ownership and business structure. Notably, under certain circumstances, a foreign entity may be deemed an FEOC only in relation to its activities within a covered nation. In other cases, entities which may appear to potentially fall into the FEOC category at first instance, may not.

The amendments that the IRA makes to Section 30D of the IRC, together with the proposed regulations and guidance, provide new avenues for Canadian incorporated businesses to take advantage of the new clean vehicle credit. This is exciting news for Canada-based entities.

The restriction on FEOCs are intended to provide more resilient supply chains for the production of clean vehicles in the US and allied nations. Manufacturers seeking access to the US clean vehicle market to take advantage of the clean vehicle tax credit must ensure end-to-end compliance with the new critical minerals and battery component requirements, in addition to adhering to the IRA's measures to restrict FEOCs from accessing the US clean vehicle market.

The Transportation & Mobility Team at Gowling WLG will continue to follow the development of the IRA and its implications for Canada-based businesses, and look forward to answering questions from readers who are interested in localizing their business in Canada to take advantage of the new clean vehicle credit under the IRA.

[1] White House, "Clean Energy Tax Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act" (last accessed February 9, 2024).

[2] Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, Public Law No. 117-169, title I, §13401(a), (e), (k)(3), Aug. 16, 2022.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, REG-120080-22, "Section 30D New Clean Vehicle Credit," 17 April 2023, 88 FR 23370, Federal Register.

[5] IRA, supra, footnote 1.

[6] REG-120080-22, supra, footnote 3.

[7] Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18741(a)(5).

[8] Department of Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, REG-118492-23, "Section 30D Excluded Entities," 4 December 2023, 88 FR 84098, Federal Register; Department of Energy, RUN 1901-ZA02, "Interpretation of Foreign Entity of Concern," 4 December 2023, 88 FR 84082, Federal Register.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

We are not qualified to practice or advise upon U.S. law.

NOT LEGAL ADVICE. Information made available on this website in any form is for information purposes only. It is not, and should not be taken as, legal advice. You should not rely on, or take or fail to take any action based upon this information. Never disregard professional legal advice or delay in seeking legal advice because of something you have read on this website. Gowling WLG professionals will be pleased to discuss resolutions to specific legal concerns you may have.